- Home

- Joan Haggerty

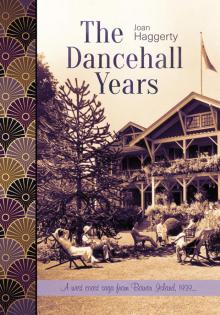

The Dancehall Years Page 3

The Dancehall Years Read online

Page 3

Oh well. His smile seems to move his face before it actually moves. The way his muscles fill up his clothes, it’s like his pants and shirt would keep their shape even after he’s taken them off.

Mostly I go up to the top court, says Isabelle. It’s not really a court.

The grass up there grows through the clay, and the marking strip’s come unstapled. No net. Only a backboard with a line painted at net level so people can practise alone.

Jack, right? she says.

Jack Long.

Isabelle Gallagher. This is my niece, Gwen.

Hello, Gwen.

When Auntie puts the racket down, Jack Long covers her hand with his so the two of them could be on the top of a cane. He looks as if he wants to carry her arm somewhere and set it free. She passes him her cream soda. Want some? He frowns at the bottle and hands it back without a word. Maybe he’s a rum and coke man. He mostly works in the grain holds on the ships, he says, where you get buried alive if you stop to blow your nose. When the band starts up, he tells Auntie to come over to the pavilion and listen to the last set.

No, she says. I like listening from here.

She does, too.

The next weekend, when Auntie comes down the hotel stairs eating cherries, Jack Long is waiting for her in the deck chair under the monkey tree.

Life’s the pits, eh? he says.

It’s not too bad. She looks up. Oh.

Don’t choke on it.

I’m liable to.

He looks as if he wants people to see him walking across the causeway with Isabelle on his arm the way her dad does when he and her mom get dressed up to go out dancing. Her parents don’t go to the dances up here, just places in town like the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club. Mr. McConnecky’s standing in the lobby window. Auntie takes Jack Long’s arm to walk across the causeway like someone putting on her lifejacket in a rowboat because her parents are watching.

Does the kid have to come with us?

She does, yes.

They take the Bridal Falls Trail the tennis court way. The water from Killarney Lake races under the white picket bridge, gathers speed to foam over the ledge. A dead tree lies on its side at the edge of the lagoon below the falls, limbs curved like thin ribs. A small oak lifts its leaves and lets them down again. A piece of water splashes up below the second white picket bridge.

Laburnum St.? That’s where you live? Jack Long asks, unfastening a cigarette package from the twist in his shirt sleeve. My dad used to fish steelhead in a stream that ran down Blenheim to the Fraser. Folks would see the fish coming, use clubs or hoes or what have you, drag them ashore. He picks up a stick, reaches down from the bridge and drags it in the water. Beautiful fish he said they were. Lucky for us longshoremen the sockeye keep running, eh?

He climbs down the ferned rocks at the side of the falls as if he doesn’t care two hoots that Auntie’s taller than he is. Takes a box of matches from his pocket, checks a piece of paper inside, excuses himself and heads up a side trail. When he comes back, he has a bulge in his pocket. The sun does its famous trick, lighting up for an instant before it turns off, then switching on as a surprise in the blackberry. The chartreuse light in the shade is a joke; it’s in the laurel behind the cedar, no, it’s come out in the salmonberry behind the hemlock. When Isabelle steps into the shade, she hugs her own arms as if she needs to have her cardigan on as much as she wanted it off a moment before when she was in the sun. The blackberries heat up when the day heats up. Someone should lift her chignon and pin it higher on her neck so it won’t be heavy on her shoulders. Her high loose knees and elbows fling up softly when she walks, as if she knows exactly what she’s doing and couldn’t care less whether anyone likes it or not.

A leaf swirls under the second bridge. Thick ivy trunks grow so many leaves and twist so many times around the host fir you can’t see the bark. The maples let a net of sun down onto the road. Jack Long ducks under a cedar branch.

Work’s better now, he says, but before the war, way too many days, I was over on Dunleavy St. in Vancouver watching my dad playing horseshoes, waiting for a dispatch to come up. This one time, the dispatcher, he’s the guy who hands out them chips, right? If you get a chip it means you’re going to work. One day, he took a handful and threw them on the ground. I was just a kid, new on the job. One of the older men told us not to go down for them, said it was degrading. So I didn’t.

A duck clicks its bill in its underwing, puffs and settles. The whistle sounds in the cove like a horn. Another time? The dispatcher put out his hand like he was going to give my dad a chip, but when my dad reached out to take it, the sonofabitch snatched his hand back and gave it to the next guy in line. You don’t forget a thing like that.

I don’t suppose you do. Do you like being a longshoreman?

You bet. I love the long northern runs the best.

A few loose dog footprints are sunk into the muddy patches of Skunk Cabbage Trail that never get the sun. Jack Long keeps talking at Auntie the way Molly won’t leave you alone when she’s trying to get you to throw a stick. If you leave without it, she picks up the stick and follows you. Isabelle looks flatter and flatter as she tries to keep him talking all the way home.

The Vancouver waterfront? Oh he’s always known the Vancouver waterfront. You know those clear windy days when the sea is that kind of dark blue…?

Cobalt?

That’s it, cobalt. Those days, aren’t they something?

Back at the lagoon, a group of red-eyed pigeons ripple pink and green down their backs. The swan on the nest closest to the viaduct coils its neck into a loop and goes to sleep.

I wonder what it’s like being them, Auntie says, pulling the hair band down around her neck like a necklace, shaking out her hair.

Mostly I guess you’re looking around making sure there’s nothing close by that wants to eat you.

Guess so.

Jack Long smiles and tries to jerk Gwen’s hand into his own so she’ll be between the two of them, but his freckles, bristly red hair and the anchor tattoo on his hand make her drop his rough hand and walk by herself.

At home on the verandah, Auntie hands him the binoculars and watches him watch a great blue heron stand on one foot, then the other. Closer, beside the wading rock, a small browner version raises both wings on what look like broken sticks and lowers them again.

What birds are those? If that’s the heron, is that a different kind of heron?

They’re the juveniles.

Oh.

Gulls stand beating their wings to dry them off. Flying away, they leave quick white streaks in the sky. A group of crows cuts the other way. Foxgloves wave their bulby fingers. Once, Auntie tells him, she brought some friends from her sorority over here, but they ran out of beds and some girls had to sleep on the floor and in the bathtub! She goes into the house to get photographs to show him the gang in their short skirts and long blouses. Two kneeling, one kneeling on the back of the two kneelers sort of thing. The ones on either side stretch their arms to the ground.

A couple of summers ago, she’d worked in the Empress Jam factory in town with her friend, Frances Sinclair, but there was no way she could keep up with blapping huge blobs of jam into cans at the pace they wanted, so they put her on folding cartons. They needed thirty every half hour. Couldn’t he just see her? He could. A hummingbird quivers with the need to put its beak somewhere. As the tide goes out, the dark grey rocks lighten. Clouds let themselves down to rest on the shoulders of the mountains.

Grandpa Gallagher comes up the verandah stairs, smiling broadly when he sees Jack. He shakes his hand, excuses himself, gently shutting the door to the house as if he doesn’t want to wake the baby. When they go in a few minutes later, he’s sitting in his easy chair by the fireplace. See that stone on the hearth there, Jack, he says. Pick it up. Mother comes to the kitchen door. She and Auntie and Grandma Gallagher wag their heads back and forth, silently mouthing the refrain. That’s where we were going to keep the family jewels,

only there never were any family jewels, ha ha.

At lunch, Jack Long is asked to stay. Grandpa hands him the jug of lemonade, the bowl of raspberries, the plate of sandwiches, watches him pour the cream. These are good. Where’d you get these?

From the Japs down on the wharf, Grandpa says. They can grow berries, you can say that for them. Never mind that they’ve taken over all the best fishing.

Get my shawl, will you dear? Grandma says to Auntie, frowning at the open back door. Grandma Gallagher’s a small woman, thin as a wren. No one makes a move to close it. Jack pulls his chair closer to Grandpa’s, dishes himself more berries, pours cream. It’s true what your father’s saying, Isabelle. Even on the docks, you know, they work for a lot less than white guys. It causes hard feelings.

Excuse me?

Japan’s made a lot of trouble in the Pacific. Look at China, look at Manchuria. You can be a bleeding-heart liberal until you come up against it, Isabelle, but from the way you’ve been talking all afternoon, I don’t think you have any idea what it’s like to be a working stiff.

Down on the beach, a duck lifts one orange leg and paddles away. A salmon jumps, and dark seedpods from the broom plants rattle in Auntie’s hand. The incoming tide softens the rockweed tips, the kelp relaxes. Gravel shell fragments swish around as if they have more room than they actually do.

Later that night, Auntie has her hand stamped at the dancehall wicket, waits at the edge of the dance floor facing the bandstand. On stage, Jack Long is looking intently at the sheet music in front of him. Maybe he’s only pretending not to notice her because, at the waterfalls, he told her he didn’t know how to read music. One of the men who’d eaten salmon at the hotel comes up to the stage; Jack puts down his saxophone and steps out onto the back porch with him. Someone comes up and asks Auntie to dance. After the song ends and her partner returns her to her place, the bench hits the backs of her knees which makes her sit down hard. When Jack comes in from the back porch, it’s intermission, and he drags her out on the dance floor as if the music’s still playing. She holds his wrist with both hands as he pulls her between the pillars across the empty floor to a spot below the special window where she stands with her fist curled against her mouth.

What’s the big idea, Isabelle? You knew the whole time, didn’t you? You heard the big managers at that lunch you told me about.

I’m sorry, Jack. I want to talk to you about something.

You knew, didn’t you?

I didn’t mean to lead you on—

I’m losing my northern run job. I can’t stay in the city, only working the one dock. You already knew a northern run would be cancelled when I started talking about my job, and you didn’t say nothing.

One of the band members taps on the air with his fist. Knock knock. We’re on. Jack holds himself still for another second, juts out his chin, turns and heads for the stage. I’ll see you around, Isabelle. Don’t take any wooden nickels, eh? That’s all I ask. Just don’t take any wooden nickels.

Wooden Nickels

3.

October, 1941

I might as well say it now, Isabelle says to her father back in Vancouver the next fall, feeding one of her mother’s nighties to the wringer washer. I’m thinking of going back to the cottage to be by myself for a while. The two of them are pressing her mother’s wet sick clothes through the washing machine rollers in the basement. Careful you don’t catch your hand in there, he says. What are you talking about? The water’s turned off. It’s not winterized. The place isn’t ours in the winter. You know that as well as I do.

Upstairs, her mother’s too weak to sit up, too restless to lie down. Her bed jacket doesn’t fit her properly if it’s up on her shoulders like that, her father says. Never been well since Evvie was born have you, dear? Some balance device gone haywire. Weeks when she continually feels as if she’s falling. Isabelle’d bruised her mother’s forearm once with a finger imprint, offended her by asking whether she was handling the pie dough too much. Sometimes she’s so frail and unstable you’d think there was a wind in the house. What’s Isabelle’s bad back from having to bend over the sick bed compared to her mother’s suffering? We have to turn her, Isabelle. You take one side of this undersheet. I’ll take the other. Now shift. You heard what the doctor said. We have to keep moving her if we don’t want her in hospital.

She does want her in hospital. She hates the standing tray cuffed over the bed. The bedside table with its amber bottles and spoons. The way her father pretends not to understand that it’s bizarre for him to be stretched diagonally on the other twin bed, holding up a new brand of applesauce that might help his wife’s constipation for heaven’s sake. Her mother’s mouth pulls thin at the edges and collapses, forehead and eyelids smooth as marble. Lavender and vomit. Apple juice through a straw

In the kitchen, he drags a piece of scum from his hot milk, dangles it from the spoon. What’ll I do with this? he asks in an overly intimate voice. If Isabelle holds the bottle of applesauce up to the light to admire the colour, the worried look fades from his face.

I could apply for the postmaster’s job, she says. I heard what’s-his-name has signed up to go overseas.

He stabs the milk scum into the sink. It’s out of the question, Isabelle. I don’t want to hear another word about it.

I’ll come in to see Mother. You know I will. There are boats, Dad, there are boats.

I told you. The water’s turned off.

I’ll get George Fenn to help me turn it on.

It’s better if people stay with their own kind, that’s all I’m saying. Whatever happened to that nice Jack fellow?

I’m going over to be by myself, Dad. Run interference between you and the hotel manager if you want to know the truth is what she doesn’t say.

Come and play Mother May I with us, Auntie. Come and play Go Go Stop. Of course she’ll play Mother May I. Of course she’ll play Go Go Stop. Since the night her father smashed her bedroom door against her bed, she’d do anything to keep him at arm’s length. Hide herself behind whatever game the children want.

She leaves the next morning when her father’s at work downtown where he manages the Woodward’s food floor. Takes a bus along the lower levels road past West Van and Whytecliff, to Horseshoe Bay and the Sannie depot. When she gets to Bowen, she makes her way down to their place, unlocks the back door and leans against it. Dark branches cross and uncross against the front bedroom window. The walls have never felt thinner. It’s much colder than she thought it would be; in a few days, the skin on the edges of her fingernails will start to split, and she’ll have to dab lanolin on the tips.

The thick firs that offer shade in the summer gloom and drip in the rain. It must be lovely and cool at your cottage, people say. You have all that shade. She props salty cushions and damp bedding on the hearth, hangs a thick comforter from the beam in the living room for protection from the north wind that blasts down the channel. She’ll have to get an oil light of some kind; the generator’s turned off in the winter. At least the cedar splits easily for kindling, and the fir bark burns in the woodstove wet or dry. Somehow she has to do something to stop her father saying anything more, so the Yoshitos won’t lose their jobs supplying the hotel with produce. She doesn’t know what but something.

The hotel is closed in the winter, but Mr. McConnecky keeps his office open and comes up on the weekends. Surprised as he is to see her, he agrees to talk to the higher-ups to see if she might replace what’s-his-name who really has left his post office job to go overseas. He’ll see what he can do about arranging for her to stay in her own cottage.

When she opens the mail wicket in the general store the first day at work, she finds the Sannie captain at the front of the line, Lottie Fenn in a pink cloche hat with a rhinestone brooch waiting behind him. The war’s in Europe, he mutters. It’s thousands of miles that way. Why are we bothering with this lights-out palaver? If Takumi weren’t sleeping in the government shed on the wharf guiding me in with a lantern,

I don’t know what I’d do.

When the customers in the queue step up to the wicket, they look at Isabelle as if it’s her fault when they don’t receive the letters they want. After work, she walks home the beach way along Sandy past Miss Fenn’s Rocky beach with its patch of higher ground in the bay that becomes an island when the tide’s coming up. Then around the point to their place at the tip. When she looks up from the beach, whether her father’s there or not, she always sees him with his hands on his hips, white flannel trousers belted high on his waist. Isabelle, please will you go down to the beach and bring me a rock the size of your foot? No cottage in those days; he’d built the fireplace first. Easier that way, he’d said, then the Union could build the cottage around it. She’d measured one stone with her right foot, another with her left, again and again until she found a flawless one that curved along her instep. Her sister, Evvie, had to go down next, find a thin flat rock that would fit as a stone lid on an indentation he’d made on the hearth. If they were going to hide the family jewels, they’d need a lid. This size, he’d said, fingers and thumbs joined to make a lopsided square. Evvie put two feet on each stair before stepping down to the next, mouth pursed and intent, coarse yellow curls massed all over her head. Back up at the cottage, she presented her father with a slip of flat stone like a piece of outsized money. He slid the lid over the indentation, and it rested there, glueless. He’d held Isabelle’s rock like a shoe brush over its spot before mortaring it into the hearth.

Isabelle’d been carrying her father’s bowling bag to the lawn bowling green when she saw Takumi Yoshito for the first time. Hunched on the lagoon shore in front of the swans, he held his hands a foot apart as if someone were rolling a ball of wool from them. He looked up, nodded rapidly for her to come and pick up the top and bottom bulrush strands of the cat’s cradle he was making and turn it inside out. When she darted over and lifted the two strands and rotated her wrists to present the woven length, they both smiled when she knew exactly what to do.

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years