- Home

- Joan Haggerty

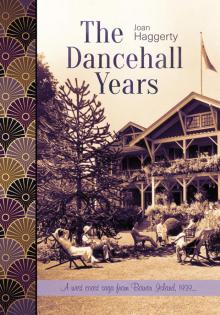

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years Read online

THE DANCEHALL YEARS

“The Dancehall Years is an elegy to a coastal culture almost lost—island cottages with views of the Union Steamships in Howe Sound, the Japanese gardeners before WWII and the terrible internments, forgotten inlets and logging camps, long summer evenings in the dancehall.’ Haggerty explores the intricate ecology of families, where memory and love are as tangled and difficult as blackberry canes surrounding the cottages, their histories echoing.”–Theresa Kishkan, author of Patrin

PRAISE FOR JOAN HAGGERTY

“The Invitation… It’s exciting to find a book so moving, sensual and compelling that getting to the end of it is both urgent and dreaded.”–Quill & Quire

“The Invitation is one of the most generous and empathetic memoirs to come out in years.”–The Georgia Straight

“Daughters of the Moon… Joan Haggerty is such a strong writer, so personal–with such prose.”–John Irving

“Daughters of the Moon… written with a lot of intelligence and skill and a strong, vital female identity.”–Marge Piercy

“Please, Miss, Can I Play God?… the impact of imaginative improvisation techniques on childhood energy is focused and told with humour.”–The Library Journal

MOTHER TONGUE PUBLISHING LIMITED

290 Fulford-Ganges Road, Salt Spring Island, B.C. V8K 2K6, Canada

www.mothertonguepublishing.com

Represented in North America by Heritage Group Distribution.

Copyright © 2016 Joan Haggerty. All Rights Reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher—or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency, [email protected]—is an infringement of the copyright law.

The Dancehall Years is a work of fiction.

Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination

or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons,

living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Book Design by Mark Hand

Front cover photo: Bowen Inn, circa 1930s, Vancouver Archives AM75-S1-: CVA 374-327. Back cover photo: Lady Alexandra docked at Bowen Island, circa 1940s, Vancouver Archives AM1184-S1-: CVA 1184-3499, Photographer: Jack Lindsay.

Reference Map of BOWEN ESTATE from a Union Steamship Company brochure, 1945, from Bowen Island, 1982-1972 by Irene Howard, Bowen Island Historians, 1973.

Printed on Enviro Cream, 100% recycled

Printed and bound in Canada.

Mother Tongue Publishing gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Province of British Columbia through the B.C. Arts Council and we acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $157 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

Nous remercions de son soutien le Conseil des Arts du Canada, qui a investi 157$ millions de dollars l’an dernier dans les lettres et l’édition à travers le Canada.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Haggerty, Joan, author

The dancehall years / Joan Haggerty.

ISBN 978-1-896949-54-3 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-896949-57-4 (epub)

I. Title.

PS8565.A35D36 2016C813’.54C2016-901040-6

For Ray Cournoyer

who built the space

Table of Contents

BOOK I

Dancehall

Wooden Nickels

Narrows Inlet

BOOK II

Take Leo

Second Childhood, My Eye

In Kind

BOOK III

Coming Home

Tide in My Ear

Buttonhole That Man

BOOK IV

The Bones of My Wedding Dress

A Soft No

Three-way Split

Hard West

Blueberries

Silverdale

Acknowledgements

BOOK I

Dancehall

1.

June, 1939

Next to Christmas, this is the best day of the year. The end of June, school’s out and they’re on their way to Bowen Island. I’m a leg man myself, Gwen’s dad says winking when he drops a suitcase on the Sannie wharf in Horseshoe Bay. Her mother’s skirt rides up her calves as she climbs back up the steep runged side of the gangplank. The flats ooze mud with clam breathing holes, and barnacled mussel shells ring the ankles of the wharf pilings. We have enough stuff for a month of Sundays, he says. What do we think, we’re going to feed an army? He piles three hats on his head to make them laugh.

The captain, white hair glinting in the sun, holds the painter of the small passenger launch like the reins of a horse. Small green waves lap the sides of the boat; the deck gives a little when you step on it. Coming up for good, are you, Gwen? he says, which means he knows you’re arriving for the whole summer and are not just a day tripper like the picnickers. He wears everything in matching navy like an old man going to private school. It’s easy to rest your hand in his palm and step gracefully on board if your parents aren’t looking.

Which they aren’t because her brother, Leo, is standing at the top of the gangplank, taking one foot on and off a rung like he’s trying to get on the escalator at the Bay. He’ll wait there until the cows come home if someone doesn’t go up and get him. Percy you go, their mother says, tucking baby Lily higher on her hip. Their dad smiles as he lopes back up to walk down with his son.

Next thing you know, they’re facing each other on the side seats of the Sannie, canvas flaps rolled down over the glassless windows in case it’s rough. Parcels and suitcases strapped to the roof. Once out of Horseshoe Bay, sections of sun glint through the clouds. Cedar and fir covered slopes smooth and darken. Near Passage Island, small sailboats tack back and forth across the channel. All Gwen’s doing is reaching out to test the temperature of the water, but her mother grabs the tail of her blouse, neck jerking forward like a grouse crossing the road.

Do you mind, Mom? I can swim.

All right.

When they arrive at Snug Cove, the launch tucks itself under the wing of the tree-feathered point. The black line of the high tide marks a bathtub ring around the stony bay. Here’s the moment the card promised when the postman tromped up their laurel-lined Blenheim St. path in Vancouver to deliver a hand-coloured photo of the Lady Alexandra sailing to Bowen Island. Lipstick red funnels, turquoise sea. Picnic crowds getting on and off. Dear Gwen, The salmonberries are ripe so I start marking off the days. It won’t be summer until you get here. Love, Auntie Isabelle. All next month and then for another, the two of them will swing in the hammock strung between the two dogwood trees, white flowers blooming like outsized stars in the green sky. The sun coming along on an invisible leash. New alders will nudge under the canvassed bulge of their bodies like small animals. They’ll hold buttercups under each other’s chin to see if they like butter.

As soon as they’re close enough to see the ochre rockweed on the beach, Auntie has to start from their cottage at the end of the point between Snug Cove and Deep Bay and make her way down to the wharf, the sun casting shadows of thimbleberry leaves onto the trail. There she is standing exactly where she’s supposed to be—hurrah—the one who comes up first to open the camp now a waving speck on the verandah. Gwen waves back, her hand a small flap that won’t stop. Last summer she and Auntie found a leaky dinghy that they rowed into the cove and sank at the exact moment the Sannie passed so the passengers would wonder how on Earth those two could be

sitting upright in the water with nothing underneath them.

Auntie’s always shy when she comes to meet the Sannie, narrowing her eyes as if to make sure they’re really family. Even when her eyes are shut, there’s a faint blue light shining through the lids as if she’s gazing through porcelain. At twenty-one, she’s tall, with pale, even skin and a long oval face. Her dress has a flounce over the seat. Her socks are rolled over her running shoes like sausages. Light cast through a canopy of maple leaves flickers over her as she comes down the tearoom hill. Mother says Auntie makes such a fuss over them because she’s looking forward to having children of her own.

Here, Ada, let me take the baby, Auntie says, lifting Lily from her sister’s arms. She holds her close and pats her back. There’s a good girl, she says. Let’s go to the tearoom and get ice cream.

Strawberry?

Strawberry.

Leo always has Neapolitan.

When you’re rowing under the wharf, people don’t know you’re the Billy Goat Gruff until you call up to them. More light flings itself on the water between the planks in strips. Just so you all remember, everyone’s on duty until everything’s done. Their mother has to say that. It’s her job. Every last item has to be carried from the wharf up past the dancehall and over the hill to their cottage. After that, they’re up for good and only the dads go down. The dads have to work all week and stay with grandparents at night because their houses in town are rented for the summer, which is too bad because renters let houses go to rack and ruin.

They shouldn’t be getting ice cream on the first trip, but no one cares. It doesn’t matter. It’s summer. The dancehall sits like a giant music box above the wharf. Ivy and wisteria climb the sides of the octagonal building and along the roof to the central cupola where the summer kids climb to lie on their stomachs and spy on the dancers inside the circle of white mock Corinthian columns. You’re only allowed to dance inside the columns if you’re in love or if you’re spectacular dancers. The floor is lined with horsehair. The grown-ups say it and the Commodore are the best dance floors in the Lower Mainland. A single leaf blows along the powdery floor. The place smells of beer, cigarettes, perfume and disinfectant from the bathrooms.

Auntie turns a salmonberry on its back, checking for worms before she pops it in Gwen’s mouth. Opened salmonberries make perfect fairies’ blankets. The places she passes through have more light after she leaves than when she steps in. When you’re alone with Auntie, she stops being shy, and acts as if life is a parade and she knows all the elephants. The fork they don’t take leads to Sandy Beach where even now you can hear the shouts of kids going down the slide double, the thighs of the one behind fastened tight around the one in front. You get a skin burn if you don’t pour a can of water on the chute before you slide down. The cool water beckons paradise, paradise.

The next stop is the resting rock, a stone shaped like a miniature North America on the hill down to the cottage. Auntie’s skin is pale—she never goes out in the heat of the day—her arm smells like the sea and the sun. The air around her is chartreuse green. The resting rock is where you cool your feet at the beginning of the summer when you haven’t broken them in yet. It’s where you sit with your face in your hands when you’re It for kick-the-can. It’s where you watch the Lady Alex coming through the cedars: black prow, trees, brass portholes, trees, red funnel, trees, red funnel, trees. It’s completely still, and then it’s all boat, a huge bulk massing out of nowhere. Fairy chariots set off between the Douglas firs in the yard of Miss Fenn’s cottage on the Deep Bay side of the point. Because Gwen’s family cottage is on the very tip, sometimes they call the area the Point Point.

Crowds of people come up on the steamer (some people call it the Lady Alex, some people call it the Lady Alec; it doesn’t matter). They sing we’re heere because we’re heeere because we’re heeeeere because we’re heeeeeeere. On Saturday nights when it’s the booze cruise, they change it to we’re heeeere because there’s beeeeere. Ha ha. The ship seems to press against their point of land the way a tall dog leans against you and doesn’t care about budging. Triangular flags on the rigging flutter like bright fall leaves between the dashing cedars. Ivy twists up the corked fir bark like veins on the back of a giant hand. On the boat, the cheering people rest their elbows on the deck railings and laugh. The sun finds a gap in the boughs, and a swath of forest lights up without a sound.

When you come up for the summer, it takes a few nights to sort out which noises are which. Chip dee do. Chip dee do dee doo. It’s only an owl. Go back to sleep. The resting rock is where you take a magazine with a picture on the cover of a lady in a polka-dot bathing suit tanning on a blanket, reading a copy of the magazine she’s pictured on. That idea would go on forever if you could see far enough. In the morning, the billowing ghost leaning against the dogwood turns out to be the drying mosquito net Mother used to strain the coffee because she forgot the percolator.

The iron cots that Mother and her younger sisters, Isabelle and Evvie, slept in when they were children still line the attic. Wooden fruit crates are nailed to the wall where you put away your shorts and t-shirts. On the verandah, a bathing cap hangs by its strap from the back of a chair. When Gwen lies on her stomach on a stool kicking her feet in the air practising the front crawl, her dad passes by with a raised hand and says, what a chance.

When she sits on the verandah stairs eating a leftover jam and bacon sandwich that Auntie saved from breakfast—her favourite—her hair flickers in a spotlight of sun so she can’t tell the difference between hair shadows and the feathery branches. The firs are nearly three times as tall as the house. Lily is put down for her nap in a cot under the Douglas fir. A crow splits its beak wide enough for a coin to slip in and caws. Funny Auntie Charlestons around the corner, wet sheets draped over her arm, a clothespin on the end of her nose. She takes more clothespins out of her mouth and marches them along the clothesline like wooden soldiers.

Name one other place, Gwen, one other location you’re cognizant of where people hang up their wash to wetten, she says.

It doesn’t take much to make the children laugh, does it? Mother says.

The Alex gets it in its mind to leave exactly the moment you’ve forgotten it’s in; the whistle makes you jump, and the steamer rushes the pram, the fan-tailed chickadees, the washing, the baby and all out in its wake as it reverses out of the cove.

One of these weekends, please will Percy get a saw and cut a few lower branches from the fir nearest the house so they can have some sun. Percy says he will, but he might not get around to it; the dads work so hard during the week they get to do exactly what they like on the weekends, which is mostly fish from the Adabelle and sit on the verandah shaking ice cubes in their rum and Coca-Cola glasses. After the dads go down on Sunday nights, the mothers laugh more. They smoke Lucky Strikes and drink coffee from cups with lipstick on them. You can jump up and down as long as you want on the living room couch. Stay on the beach until the sun goes down, watch slips of turquoise in the sea turn silver, no they’re green, no they’re silver. Logs float in the bay you can swim out to and claim, paddling flat with your alligator hands. Crabs scuttle under new rocks when you lift up their houses. Leo takes the wheel on the ship log. Blue forget-me-nots grow in the crannies. Take us to Bowyer. Take us to Anvil. No, take us to Passage.

High tide in the morning is way different from high tide at night. When it’s high tide at night, the water feels like it’s going to stay in while you sleep; in the morning, when it’s in, you know it’s going to turn around and go straight back out. Waiting for a grown-up to take you to the beach must be the way their springer spaniel, Molly, feels when no one wants to go for a walk and she’s left pawing at the air. One sec, Auntie says, while I water these azaleas. There are no miniature people behind the lit fabric on the radio. Leo says only babies think that. Past where the sword ferns tuck into rock crannies, sunlit gold coins shimmer between the waving boughs. The next tree turns off the switch. If you furrow

your fingers into purple foxglove blossoms, crouch below the cottage window ledge, stick up gloved fingers one after the other and bend them down again, Auntie will look up and laugh. If you do it faster and faster, it will be funny enough for her to come over to see who’s masterminding the show. By then, you’ll have ducked so far down she’ll think it was the fairies.

After she’s watered the azaleas, she says she won’t be long, she’s just got the petunias to put in. Who cares about the petunias? When Mother takes her to the beach, all she does is sit in the shade, only coming into the water to breaststroke a few yards, lifting her chin to keep her head above water so her hair won’t get wet. What kind of a life is that?

In the end, there’s nothing to do but go to Sandy on her own, hang her clothes on a hickory limb and not go near the water. Sit on the concrete stairs and wait. If she can make everything hold perfectly still, grasp her wishing self tightly enough, the longer she doesn’t let herself look, the more likely it’ll be that, when she does look, her swimming teacher, Takumi Yoshito, will be standing on Sandy as if he’s always been on the beach and summer can begin at last. The cork ropes that should outline the swimming area will be coiled by the racing wall ready to be pulled to the wharf in the rowboat. The door to the lifeguard shack will be open, the blankets tucked firmly into the cot. Charts posted showing rescuers pressing the backs of drowned people so water can pour out their mouths. The huge beach thermometer that’s hopelessly exposed when there’s no tide to measure will be decently covered with water, and Takumi will be raking sea lettuce along the high tide line, his tender smile wandering more to one side of his face than the other. Even this far away, you know that when he catches sight of you heel toeing along the narrow board that tops the backrest down the length of the beach, you’ll be able to swing on a star. His sweatshirt slopes down to his narrow hips, and his eyelids fasten flat against their sockets, not like her dad’s that fold back like an accordion. Takumi acts as if teaching children to swim is how he always imagined grown-up life. As if he lives to shape their keels and set them afloat like boats.

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years