- Home

- Joan Haggerty

The Dancehall Years Page 2

The Dancehall Years Read online

Page 2

There he is standing in the water up to his thighs, the deep note of his voice ready to sink soft and low in the back of her head. Her neck turns as if it’s been oiled when her head drops into the silky sea. If you believe in the sea and pretend you’re in your own bed at home, he says, the water will want to hold you up. Lying below him, the current streams through her hair the way it did when she was allowed to have it out in ringlets that dropped from her mother’s fingers like laburnum blossoms. ‘When Takumi slides his hands from under her back, the magician in the shiny blue suit at the vaudeville show spreads a cloth over the girl lying on a table and she disappears. One of his hands strokes the air above the cloth from her waist to her feet, the other from her waist to her head. She has to grab his upraised wrist so he can yard her straight out of the water, flashing her up with the spray until she’s flying like a fish.

You were swimming, he said. You were swimming.

2.

June, 1941

This summer nothing’s like it’s supposed to be. Not one thing. Their mother’s parents, Grandpa and Grandma Gallagher, are at the cottage already, which means they have to mind their Ps and Qs in no uncertain terms. Meals will have to be on time, no ifs, ands or buts. It’s their house, mother says. Who else built the fireplace? I ask you. At the wharf, no one’s making bets about the number of trips it’s going to take to the cottage. Nothing about ice cream at the tearoom and what flavour it’s going to be. The only thing to do is tuck yourself into the adult formation and let them take you along willy-nilly, even if it seems like what Auntie wants is for everyone to keep walking to the end of the point, wade into the water and keep going so not even their heads reappear.

When they get to the cottage, the grown-ups line up on the verandah and stare down at the beach. The tide’s so far out the distant rocks encrusted with barnacles look burned. No one says, If you kids are going to eat watermelon, go and lean over the verandah. No one asks for anyone to come and look at what she’s been doing in the garden. Someone’s hand on the table, someone else’s on top, then another’s, faster and faster until you don’t know whose hands are whose? Not this year. All you’ve got are a bunch of umber ponds in the intertidal zone that will have disappeared by suppertime. It’s as if they’ve passed their own stop on the tram and don’t have a chance of finding their way back, like the time before their dad was married when he fell asleep coming home from dancing downtown and the conductor had to wake him at the end of the line. He fell asleep again and ended up going from one end of the city to the other all night long!

On Sunday mornings before Lily was born, Gwen and Leo used to walk to the store holding their mother’s hands. Paths furrowed along Salmonberry trail that weren’t there the night before. The grey mass of beach at Sandy was carried over as ballast in the Lady Alexandra when it came from Scotland. A freighter is built to carry freight. If you don’t have any freight to bring from Scotland, you put sand in the hold. Crushed ferns, rum bottles in the grass. Drunk people who missed the boat asleep in the woods. What they’re supposed to remember in cases like this is to walk along as quickly as they can and pretend not to see. A lady always knows when to leave the party. A lady can always pretend not to see.

That night after the moonlight cruise steamer has docked and the music from the pavilion is drifting down the hill, Gwen lies in bed in the attic listening to the adult voices up through the gap by the chimney. Grandpa Gallagher is holding forth in no uncertain terms that Auntie Isabelle should not be gallivanting around by herself on dance nights and where on Earth could she have got herself to?

She’s a big girl, Dad, says Mother. She can take care of herself.

She’s not as level-headed as you are, Ada.

The trouble is it’s the war now and not one of those summers when it’s easy to remember that, when the sun comes up, it’s really the Earth curving away and not the other way around. That it’s the tram on the track beside you pulling out, even though it seems you’re the one doing the moving. If she’d been able to hold that fact in her mind a bit longer, maybe she’d remember whether or not the moon rotates as it’s going around the Earth. If she climbed down the fire escape ladder nailed to the side of the house, it would only be a ten-minute walk through the woods to the small meadow beside the dancehall where she could chin herself on the window and see what the dancers are up to. She can’t go to sleep anyway without Auntie on the other side of the partition calling out sweet dreams. Sleep tight, don’t let the bed bugs bite. She pulls up Lily’s blanket on the cot beside her, makes sure she’s sound asleep, puts her underwear back on so she can tuck in her nightie and not trip climbing down the fire escape ladder from the attic. The full moon lights her way along the path to the edge of the small meadow where she’s about to start up the grassy hill to the pavilion, but ahead of her, she almost trips and has to back away from the forms of two people lying in the grass. Grandpa’s footsteps pad along the nearby trail. Fear spreads below her diaphragm like water oozing under stones on the beach when you pick them up and the crabs have to run away to find new houses. People from the dancehall pass by, hollering it seems like to nobody. She can see that it’s Auntie lying there all right, but whoever she’s holding in her arms has his back turned. The wharf lanterns corkscrew their beams into the dark oily water.

The next morning, Grandpa slaps down magazines with pictures of soldiers kissing their girlfriends. All people have to know is how to behave! he shouts. Later, after Auntie snuck back in, he’d pounded up the attic stairs and slammed her door so that it whapped hard against her bed. Don’t think I didn’t see you over in the shadows, Isabelle. What if you don’t get your period? he shouts. Why would he be getting mad at her for forgetting what’s at the end of a sentence? At breakfast, Auntie winces his hand off her shoulder, and he hits the table for no reason. I’m going to work, she says. Gwen’s coming with me. I need her. She needs me. She runs to the shed, stuffing pots of red geraniums into cardboard boxes. Take these, Gwen, and these. My wretched father. He darn well could say anything to anybody. Lily wants to come with them, but Auntie tells her she has to stay at home because she’s a tagalong. The two of them march over the causeway bridge that separates the lagoon from the saltchuck, along the trail past the honeysuckle and wild rose arbours. At the greenhouse behind the hotel, they stop in front of the head gardener, Mr. Yoshito, who’s sitting at his garden desk peering over his glasses. A few seed envelopes are stuck in his hatband. A picture of his son, Takumi, rowing his lifeguard boat has pride of place on the desk.

Flowerpots are stacked inside each other behind him. Mr. Yoshito is famous for collecting rare plants from all over the world. Smell this, he’ll say and slide a magnolia grandiflora under your nose. Grandpa Gallagher is the gardener of the family and says he doesn’t know what he would do without Mr. Yoshito’s topsoil. Very - nice - soil - you - have here, he says, breaking up his words, which makes Auntie frown. Once, when Gwen was sent to the store to buy a tin of Old Dutch cleanser, she was so busy looking at the nun with Dutch shoes on the label she tripped on an uneven wharf board and scraped her knee. Mr. Yoshito came out from behind his vegetable stall, told her to straighten her leg and smeared balsam pitch on the cut. She kept staring at her knee all the way home because she was used to getting bawled out if she got pitch on her skirt or shorts. Up at the hotel, Mr. Yoshito takes flower bulbs from his pockets and fastens them in the ground like doorknobs.

Now, at the hotel greenhouse, Shinsuke Yoshito doesn’t say a word about the geraniums; instead jumps to his feet and strides up and down the spicy aisles, picking suckers from the tomato plants. He takes in all of you at one glance, and doesn’t suffer fools gladly.

I was thinking maybe we should plant water lilies in the lagoon, Auntie says, following him.

Water lilies spread way too fast. You know Beaver Lake in Stanley Park? A few decades from now, they’ll be dredging it at exorbitant expense because some idiot got it in his mind that water lilies are picturesque. Yo

u have to remember, Isabelle. You and Takumi aren’t children anymore. He shoves a box of cherry tomatoes along the counter. I told your father I’d send these over. If you want to help me, do what I tell you, Isabelle. Just do what I tell you.

So her dad has said something, I can’t believe it, she mutters on the way out the door. How early did he get over here? He must have got up before the sun. Bloody hell.

Auntie.

Sorry, Gwen. Excuse my French.

Walking from the greenhouse down to the hotel, it’s like a cube of glass forms around Auntie’s head and balances on her shoulders like a pot. What ho, Gwendolyn, calls Miss Fenn from over the fence at the lawn bowling green, dipping her knee in a curtsey as she lets go the ball on the manicured lawn. Besides being their neighbour, Miss Fenn is the school teacher; it’s strange to think, but she stays in her cottage all winter with only her cats for company. She wears white ankle socks and Cuban heels, lots of pale powder on her face shaded by a veiled hat that dangles a long white chiffon scarf. At the lawn bowling green, they have to wear all white. When you see her coming across the causeway, Auntie says you can tell she thinks she’s in the Easter Parade. Miss Fenn always calls Gwen Gwendolyn. People say it isn’t summer until Mrs. Yoshito and Miss Fenn have delivered every last flower basket to every single resort cottage. Double geraniums for the First Aid Station, double geraniums and extra lobelia for the Deluxe cottages at the back of the hotel. That’s what makes them deluxe, Miss Fenn laughs. When you press your hands on the lawn bowling green, the surface rises back up as if it’s never been touched. Plum trees grow on three sides of the surrounding bank. The bowlers whisper to each other as if they’re in church when the balls hush themselves along the grass. The honk of a trumpeter swan expands over the bay, flattens and dies.

Guests come through the hotel’s glassed-in porch and stroll down on the lawn. Lovely day. Isn’t it? they say, congratulating each other on the weather. The hotel manager, Mr. McConnecky, has skin, a moustache and hair that are all the same kind of fleshy pink. He leans over Isabelle’s typewriter as she types the new brochure. Salty coves and rushing waterfalls. Sunny spots and where to find them. The salt coast Riviera? Is that what you want me to say? Auntie asks. Today, her brown hair is braided in a crown above her worried forehead. I thought the sun coast Riviera, says the manager. But leave it in, dear. The dining room has tables with white tablecloths and folded serviettes like party hats. At lunch—Gwen’s allowed to pass out the menus—the general manager who’s over from town for the day says he’ll take the cold salmon mayonnaise. He hands off his menu to Auntie, turns to the man beside him who’s what they call a silent partner visiting from England and is tucked beside him like the dormouse.

The northern steamship runs are all different now, of course, with the tourist industry down, the general manager says. It’s a good thing they’ve got Bowen here to concentrate on. No gasoline money, so it’s a nice short excursion for people. Moving servicemen around, they’re not having to haul as much cargo north the way they were before. It’s a nightmare travelling with only navigation lights. No two ways about it, they’re going to have to switch some of the longshoremen to the local runs.

I’ve never seen mauve roses before, says the general manager’s wife who is very pretty.

When Mr. Yoshito passes under the front window, his glasses mirror the blue hydrangeas. Auntie looks frightened as if a small furred animal has leapt under her dress and crawled up her calf. The general manager’s wife says she does want to see the gardens. They’re only here for the day.

We’d better join the ladies. Otherwise, it’ll look…

I guess it will. Is it still raining?

After lunch, Mr. McConnecky, the dormouse and the general manager take their seats in wooden deck chairs under the monkey tree. Garter snakes that Leo says winter underground in circular clusters slither in the grass. It’s because Leo’s always thinking about science and how things work that he gets stuck places like on the gangplank to the Sannie wharf. Mr. McConnecky waves as Auntie passes. Tennis balls splat on the courts. Gwen xylophones a stick along the slats of the honeysuckle arbour where Mrs. General Manager and Mrs. Dormouse emerge blinking under their hats. Some people’s children, they say.

At the end of the lagoon, the wives from the luncheon party hike up their dresses so they can wade in the brown water. Maybe they would like to hear the man in the tuxedo who plays the spoons at the afternoon concert in the vaudeville bowl. At the lagoon, Auntie is concentrating on chucking tomatoes into the water when a red-headed man with freckles all over his back dashes up the causeway and asks her if she’d go in the three-legged race with him. They’re holding the start for us, he says.

Oh, I’m not on the picnic, she says as the haze along the Sound blends the horizon of the sea and the mountain to a dusky blue. Then. What the heck. Why not? Auntie pushes herself off the wide cement railing and strides beside him to the starting line at number one grounds by Sandy Beach where they drag each other the first few yards, the skirt of the flowered sunsuit she changed into after work flies as their joined middle legs pump together and their outside legs kick in. After they cross the finish line, she unties the knot of the scarf pulled tight around their ankles. Would she like to come over to the Longshoremen’s picnic at number two grounds, have some potato salad? Oh I can’t, she says, I have to get home. But thanks for the race. She turns up the trail, leaving him empty-handed like a dancer in the dancehall when his partner walks away.

When they get home from the race, Grandpa is lifting the heads of creamy snowball plants, so waterlogged from all the rain their stems bend to the ground. He lets Lily shake them, but she’s getting herself all wet. If you let morning glory climb the hydrangea, it chokes the whole plant.

Have you noticed how carnations smell like cloves when they’re wet, Dad? Auntie says, smelling the ragged magenta blossoms as if it’s dangerous to even look up.

Cloves? Grandpa asks, standing there in his lawn bowling whites, the white and shade of him the wrong way around like on a picture negative. The way his mouth is high up above his chin makes him look like a picture in a book where you have one of those old-fashioned adult heads on a child’s body.

Grandma Gallagher comes up the path from the beach, carrying a pile of sheets with stained corners where the clothespins have mildewed. When she bends over a pail to deposit cigarette butts people have thrown off the porch, you can see blue veins on the backs of her legs. Only impatiens can bloom at their cottage because it’s all shade.

Nobody’s irreplaceable, Isabelle, Grandpa says. Remember that.

Auntie jerks back as if she’s been lassoed, tries to get her foot on the stair and misses. On the beach, gulls perch one after the other down the line of boulders. Brittle tips of rockweed mark the tide line. The rusty frayed end of a loop of cable is caught under a rock. After the race, the red-headed man had looked down at Auntie’s ankles as if he wanted to pull up the backs of her socks so they wouldn’t slide down inside her running shoes.

After supper, Auntie takes a bowl into the back bedroom and smudges soap in her armpits with a thick brush, pulling the razor down hard so her skin stretches like a chicken’s spread out thighs. This must work if it’s what men do every day, she says, scraping bits of hair into the basin. The mirror has a jagged flaw. She thumbs up her eyebrows to pluck under them, yanks out a few nostril hairs, nose going one way, mouth the other. Drops a white pleated skirt over her head, ties a matching headband around her forehead until not one piece of hair shows. Tucks her tennis racket under her arm. The arbutus trees roll back their auburn bark like stockings. As she walks up the hill, she picks her feet up higher than she needs to. One arm swings at the joint as if it’s loose. At the corner of the dancehall and tearoom, the ground is scuffed with tiny pinecones.

The verandah of the tearoom is so wide people could dance on it. Sometimes they do. Customers inside drinking milkshakes tie their dogs to the balcony railing, but the dogs bark and the

owners have to bring their milkshakes with them and take the dogs for walks. Isabelle arranges herself on the wide railing, droops for a moment as if she has no bones, gently curls the back of her hand against her mouth. She lifts one knee with both hands as if it’s broken and her palms set it in place. Her face flutters when she looks away before it settles into a new position. She arches her hands on top of each other and puts them on her knee. (She sleeps with her arms crossed over her chest, hands cupped like tulips.) Inside the tearoom, two girls are standing at the counter, buying toffee in a package with a pretend plaid bow. That saxophone player? The one with the sandy hair? He’s really good. Maybe he heard you, they giggle, as the man from the three-legged race comes up the stairs. All of him is there to see, Auntie, not just his face.

I didn’t know you were in the band, she says.

Oh, you know. Keeps me off the streets. He picks up her tennis racket, leans the mesh on his palm. These cat gut?

I don’t think so. Are they supposed to be?

I don’t know. I thought they were some kind of cat gut.

She takes the racket from him, pretends to swat a ball. He turns and pretends to see it rolling along the ground.

You work at the hotel, eh?

How’d you know?

Oh you know, asked around.

It’s pretty hectic right now. Management, managements’ wives, trustees, silent partners from England, you name it. Talking about re-rescheduling steamer runs, thinking of cancelling some, so on and so on. She takes the racket back, sweeps her arm in a wide arc, wrist turning like in an arm wrestle match. Look at my stupid forehand. I darn well always do it like this. She serves as if her arm has been lifted straight up on a string attached to her wrist. Then it collapses.

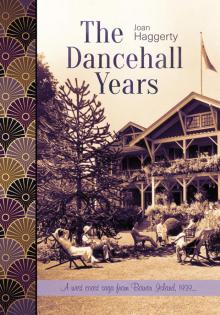

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years