- Home

- Joan Haggerty

The Dancehall Years Page 4

The Dancehall Years Read online

Page 4

The next day, she and Takumi swam together at Sandy for the first time, walked along the dusty road hitting each other’s knees with their towels. Mrs. Yoshito pulled up in the only truck on the island. Noriko Yoshito was so small that, when she leaned over to open the door for them, she had a hard time keeping her foot on the brake pedal and unfastening the lock at the same time. Strange, isn’t it, she said, the way a person runs out of things at the worst possible moments? She looked embarrassed to be in her apron as if they’d caught her in a négligée. All the way to the store when all I needed was a last bit of paraffin for the canning. She patted the seat next to her for Isabelle to sit down, the cushion warm and ready. Come and have lunch with us, she said as Takumi climbed into the truck bed and made funny faces through the back window.

Like when you run out of thread the last inch hemming something, Isabelle chirruped back, wanting to be on a par with this mother who has not been lying in a sick bed with a wet cloth over her eyes off and on for years, who could push a floor gear stick into position with her wiry arm, straining her neat face up over the steering wheel.

They turned onto the Miller Road, and around the Millers Landing corner to Scarborough Beach where the Yoshitos lived. As they clattered down the rutted driveway to the large handsome white tongue-and-groove house on the sea, a trumpeting morning glory spread wildly over the seashell path. Geese flapped out of the way, the peak of the house split the light, and waving sword ferns beckoned them in. Mrs. Yoshito jumped briskly out of the truck, hurried into the kitchen, grabbed her oven gloves to pick up the canner as if she’d never been gone, carried it to the sink to drain the salt from the piccalilli. Picked up tongs to lift hot jars from the steaming water bath. Six hands she said she needed this time of year. A small wooden man and woman announced the time one after the other from a cuckoo clock.

In the dining room Mrs. Yoshito stopped in front of the sideboard, rang a small bell, carefully placed it back on its tray, then lit small candles and strange smelling sticks. Poured water into a tiny dish, propped flowers in another and offered huckleberries in a third. Smiling as if the offerings themselves had turned on the glow in the shining wood table, she held out a chair for Isabelle and waited for her to sit down. A huge plant with leaves like soft green moose antlers hung from a layered papery bulb. Birds of paradise decorated the porcelain cups in the china cabinet. Stained glass windows and a scroll of writing with the moon in it hung above two clay urns placed either end of the oak sideboard. Mrs. Yoshito went out, returned and presented the soup. Her hair was shorter on the back of her neck than along her cheeks. Rainbow patterns wavered over the surface of the urns. This is kombu, she said. The seaweed you kids know from the beach.

She ladled the soup slowly, placing the gleaming bowls in carefully chosen positions, as if the polished table were the background to her perfect creation. Isabelle looked with delight at the birds on the cups, high enough in the china cabinet to sing to her from their branches, moved her chair down to the corner of the table where the etched grain of the wood surface swirled into a shape of wings, then cupped her palms over the spot where the grain coalesced into the pattern of the eye of a bird. Mrs. Yoshito picked up her hand, gently turned it over as if she were going to tell her fortune, then threaded two chopsticks between her fingers and showed her how to open and close them like a beak. The three of them bowed their heads over the soup, said ita daki mas, as if each time the family came to the table to eat, they gave thanks for the warmth of its presence and each other.

After lunch, they walked up to the fields where the berries ripened: the strawberries first, the blueberries, then the high hedge of blackberries in the west. Throwing in boards to break a path, Mrs. Yoshito plucked at the bushes so fast it was as if she were milking them. Later, they walked the path to Bridal Falls to start the pump that started the generator so that, over in Deep Bay, people at the hotel and in the cottages could listen to the news.

After that first day, Isabelle and Takumi played together all the time, running around the point and the cove, in and out of peoples’ cottages as if they owned the place. Sang for his baby sister who got born dead by mistake, which is why his family had to divide her ashes into two urns in case one went missing. That way, she could eat in the dining room with the family every day whether she was alive or not. Singing in the treehouse that Isabelle’s father built for Miss Fenn in the curve of the cedar that leaned out over her rocky beach, they watched the tide come in until only one piece of high ground was left in the middle of Deep Bay. Then there was only a bright green patch of seagrass, which flourished because it was hardly ever under water. When the tide was at its highest, even the grass was covered.

Once the Gallaher’s cottage was built at the end of the point (and the family moved out of the tents under a real live roof), the two of them conducted singsongs in the attic, pulling sheets between their legs to coil into birds’ nests. Burst into Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah each time Takumi’s sister got born in the baby shiners they squeezed from the mother fish down at the pier and dabbed one by one along the boards.

Until one day in the treehouse, their hands changed from pretend crabs scuttling over each other’s faces into palms moving to each other’s mouths to be kissed. When Isabelle’s father whistled loudly for her to come up and help him with her mother, the pirate ship they were riding sank into the sea. The chariot clattering through the meadow lost a wheel.

I don’t know what I’d do without you, Isabelle, her father said at the top of Miss Fenn’s trail to Rocky. We have to go home. Your mother has to lie down. She needs a facecloth on her headache.

Now, back on the island in the early spring, gumboots sinking into mud with every step, Isabelle restacks last summer’s wood and hurls chunks of wet alder under the verandah to dry. She’d had to tell Takumi when he came to the post office that he couldn’t come to the cottage, she couldn’t see him. She’d told her father she was coming over to be by herself and he’d know. He’d just know. I always know where you are, Isabelle, he’d said. Sometimes I don’t like it but I know. He’d speak to the higher ups. They’d lose their jobs. He knows about us. Takumi, I have to do what I said I was going to do. I can’t lie to him. Please.

One afternoon after work, she smashes her old fedora on her head and goes down to pick clams to make chowder for supper. Get back in your shells, you little suckers. In the pail with you. Up at their cottage, a shadow that’s probably a piece of furniture shifts on the window pane. When she looks up again, she sees that it’s Ada and the children of all people. Gwen, Leo and Lily are standing on the gumshuwa at the bottom of the trail. We’re here to see you, Auntie! And it’s not even summer.

In the kitchen, she finds Ada fussing around saying she doesn’t mean to sound put upon, but Isabelle knows perfectly well this is the last thing she needs, coming all the way over to Bowen in the winter when Percy’s so busy in Vancouver making engines for the war effort, and their father’s rattling around Laburnum St. all by himself. Their mother has to be visited in hospital every day, as if Isabelle doesn’t know. Ada’s thickened at the waist, has to lift her gabardine skirt a touch at the thighs to sit at the kitchen table. This place is a freezing cold box, she says.

What are you doing dressed like that, Ada? You look like you’re going downtown. Don’t you hate it when you leave a cupboard door open and bang your head on it?

Working the tablecloth between her fingers, Ada keeps frowning at the wonky blanket stitching around the edge. This looks a bit worse for wear, she says. Put that bucket down, Isabelle. What have you got in there?

Clams. I’ll make chowder for lunch. Cut up some celery, will you?

The children don’t like clam chowder.

I’ll open a can of chicken noodle for them. A spider in the chowder pot has to be shaken out the window. That’s good. They eat aphids. Do you ever think what it must have been like for mother when there was only a tent here? Wasn’t it the doctor who said she had to get away and have a holiday?

What kind of holiday would it have been with three children? Ada’s knuckles move back with the celery; she forgets to stop at the edge of the board and cuts at the air before she fiddles the bits into the bowl.

It was nice of them to leave you some clams, I must say.

Pardon?

The Japs. At least they haven’t cleaned out the whole beach. They eat everything you know, all the fish guts.

Are you doing this on purpose, Ada?

I mean it as a compliment. You don’t have to look at me like that. I guess you haven’t heard. The Japanese are being put away in camps. It’s the only safe thing to do.

What did you say?

The Japs are being sent to the Interior. Because of Pearl Harbour.

But it’s only the people in Vancouver?

I don’t think so. Just come home, Isabelle. This is no place for you in the winter. Are you going to come back on your own, or am I going to have to send Percy over to get you?

In the mail queue, pent-up slurs are given voice as if permission and credibility have been granted now that the news of the internment is official. In the fall, they were saying as to how Shinsuke Yoshito was the best gardener in the Lower Mainland; the Stanley Park gardens didn’t hold a candle to his beds, but now phones are lighting up of their own accord. The day my son came home from school saying Takumi Yoshito got his best marbles off him in the recess game? Won them fair and square was what I thought at the time, but maybe I was wrong not to side with my son. What’s Yoshito Senior been doing over there sitting on his verandah with those high-powered binoculars of his, eh?

A night comes when, down on Miss Fenn’s Rocky where she’s getting more clams, Isabelle looks over at the causeway bridge and sees Takumi running toward her along the low tide flats. He’s almost there, then not there yet, then closer and closer until he’s falling into her arms, his mouth opening and closing with no sound. She loves him so much she’d lift his folded length and carry him anywhere he wants to go. Anywhere. Suddenly, nothing else matters.

I’m not afraid, Isabelle. Where do I go to enlist? I want to sign up.

I heard about the evacuation order, she says. Ada came up to tell me. It’s only the people in Vancouver, right?

No. It’s everyone. I’m not going.

Of course not, you’re not going.

She places one hand either side of his face. Come tonight and we’ll talk. Don’t leave me. Don’t ever leave me.

When she looks up and sees him standing in the doorway of her cottage, he steps toward her as slowly and surely as the tide below them would find its way to the winter high mark under the house. Each of his footsteps contains all the footsteps he’s taken in the years they’ve known each other. They wrap their fingers in each other’s hands as the winter sea below them tries to soften the stones. Woodpeckers fly diagonally in front of the beach, wings flung backward. A long caw from the fir branches, then silence. When he pulls her to him by the small of her back, her vertebrae mount on top of each other like the small stairs in the woods by the falls they’d climbed the first day they met. In bed, she nervously folds her nightie up from the hem in small pleats, raising her eyes over the horizon of her breasts to watch him unfasten the buttons on her nightie, then start on her cells. Not hearing from you is a desert. There are no houses, no trees, no people. He is her brother, he is her child, he is her beloved.

A loon tucks his head and slips into the water, the way he eases out of her afterwards. She lies with him in her arms, his head on her breast. Never stop looking at me like that. Never stop telling me what you’re going to do next. Talk to me. He smiles in his sleep as if he has as much confidence in the covering and uncovering of the life between their bodies as he does in the emptying and filling of the bay below them. If he leaves a trail of crumbs behind him on the way to her house, she’ll go out at night and pick them up. In the city, people pull their blinds down and seal them with tape. Black eye patches with slits cover their car headlights. If he pretends to be concealed by her, the announcement will never have been made. He’s sleeping where he said he would be sleeping, in the shed on the wharf with his lantern dutifully guiding in the Sannie.

That night, Isabelle dreams she has to pack her father’s binoculars, bowling balls and white flannel trousers. There’s going to be a terrible flood. She’s not supposed to have his things, only her own. What’s she doing with his binoculars? Where did she get that dollar?

In the early morning, Takumi sits up in bed drinking the coffee she brings him as if he’d been shipwrecked and barely made it to shore. A faraway light on the horizon shines through the trees. The moon is in shards on the sea. The embers in the fireplace flash on and off: the last log glows underneath. Night will gather at the start of the day, massing at the horizon to bring them cover as their limbs move together, fluid as coho. The light from the last log in the fire softens lines between their bodies they don’t know about yet.

Except that there’s a knock on the back door, and both of them startle up. Pulling on her dressing gown, Isabelle opens the door to find Noriko standing there in her hat and coat. She looks three inches shorter, as if gravity has doubled its pull since she last saw her.

Some people had to leave so fast they left food on their plates.

They’re taking us away, she says. The officer said I could come and give you the key to the house. Take care of everything. We won’t be gone long. She turns and looks up the hill.

Of course you won’t be gone long, says Isabelle. It’s all a mistake. It’s just this awful war.

It’s just this awful war. Where’s Takumi, Isabelle? Do you know where he is?

I do, yes.

Tell him they’re looking for him. Take care of him, do you understand me?

I will. Look after yourselves. Please. Isabelle reaches for her, but there’s nothing there. Back in the bedroom, Takumi’s sitting on the edge of the bed with a look of collapsed loneliness she’ll never forget.

That was my parents, he says. I have to go.

No, you don’t have to go. We have to stay calm and think this through. We’ll figure out something.

He pushes her hands away, grabs his shirt off the floor, rushes up the hill after his mother who holds him tightly, then pushes him away.

Get away from here right now.

I can’t let you go without me.

They said we have to be detained, Takumi. Try to sell the house. It doesn’t have to be for a lot. Sell it to someone who’ll sell it back to us after the war. Get it in writing. Dad and I will be counting on you.

I’ll find out where you are and get you out somehow. Tell Dad I’ll look after everything. It won’t be for long.

A quick embrace and she’s gone.

That evening, palming their flashlights, Takumi and Isabelle meet at the Yoshitos’ Scarborough house, pack all the warm clothes and dried food they can fit into a knapsack. She stuffs in more rolled socks, hangs her swagger tweed coat in the bedroom closet to protect the place when she’s not there. They leave silently, and he turns up the trail to Killarney Lake where he’ll spend the night.

Where could you go, even if you do get away? she asks.

North.

They’re going to find you. They’ll be watching the coast.

Inland then.

I can’t let you go.

You have to let me go. I’m not going to any camp. I’d die first.

Promise you’ll come and tell me where you’re going.

I can’t promise you anything. All I’m asking is that you look after the house.

I’ll do my best.

Not your best. You’ll do it. Let go of me, Isabelle.

In bed, back at her cottage, every cell in her body on alert, she matches her palms flat together and winnows them between her thighs like a child in shock. Searches for the notes in her fingertips that will let her know he’s still with her, that the spider legs of her fingers have been left behind for her to use. I have a lover. I feel like a piano. She ho

lds her hands where his shoulders should be, his head should be. She’s self-sealing. The darkness is everywhere. If she can see him clearly enough, smell him deeply enough, press herself on his mouth at exactly the right angle, he’ll be with her forever.

The next day, getting supplies out to him is all that matters. Already she feels people are watching her. Miss Fenn, say, the only other person on the point in the winter, but quiet as Takumi was, she might have seen him come in. The Yoshitos lost their jobs anyway, no matter what Isabelle did.

It’s so cold and rainy the next day when she heads back to the Scarborough house to get more dry clothes for Takumi, she automatically pulls more straw and moss over the strawberry fields for mulch the way Mrs. Yoshito would. The varnished ball supporting the sweet peas has rolled off its pedestal. The fields are trodden over and wet spoked maple leaves heeled into the ground. The white rose bushes Mr. Yoshito planted on the other side of the fence, so anyone looking out the window would see cascading blossoms rather than roots and stems, are pulled up and tossed out to die. The padlock she and Takumi hooked on the front door is sawn through with a hacksaw. Inside, everything has been taken from the china cabinet and thrown on the floor. The windows in the dining room alcove are broken, the upstairs mattresses slashed. DIRTY JAPS scrawled on the upstairs wall. Their precious table is heaved on its side in a corner. She walks from room to room crying, picks up a ripped kimono and hangs it up. The good porcelain is gone, the family pictures in the alcove shredded. The sofa slashed. Someone has even taken sections of the oak floor. Splinters of window glass crack like shattered ice, the smaller bits powdering into dangerous sand. Jagged sections stick in the frames.

Still crying, she scoops the heap of ash back into the urn that’s fallen on the floor and takes it with her for safekeeping. The urns are too heavy for her to carry both so she places the other urn carefully on a high shelf, hiding it behind some books. Covering the gaping window frames with plywood, she goes to the store to buy a sturdier padlock. That night as she’s sitting numbly by the fire, she sees Takumi coming up the verandah steps of her cottage under the stealth of the moonless night and the cedars.

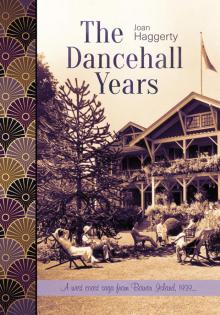

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years