- Home

- Joan Haggerty

The Dancehall Years Page 25

The Dancehall Years Read online

Page 25

She could feel that he’ll go the distance until she could see what? Something neither of them knows, but she does know that, whatever it is, when she does find out, he’ll care.

One evening, spring has settled in with such certainty Gwen and Derek find themselves down on the beach after the kids are asleep. The rhodos and azalea are almost out. The smell of the sea lettuce is pungent, the long grass whispers in the meadow. It isn’t fair they get along so well. If he leans toward her, his soft beard would stroke her breast. And his moustache. There has to be a moustache. That frisson, eh? If she weren’t attracted to him, it would be no contest, but in the same way the planet goes on turning away from its star, everything at that moment feels so exactly right she wants to cry. Is it part of getting older that everything has to be exactly right? Say he reached out and put his hand on her hair. (I really do try to live up to all the hard work you’re putting into me, she said to the doctor.) If he did, she’d put his hand carefully back on the sand and tell him the opposite of what she wants to say. And then he does touch her hair. And then she does put his hand carefully back on the sand.

I’d better get over to the hall and help with the sanding, she says.

Oh leave it. Tomorrow. His eyes beg.

I’d like to but I can’t, she says. Look what might happen to what we’ve got going here. It would confuse the kids even more than they are.

The kids don’t have to know.

That’s how it always is at the beginning.

I want you.

You think I don’t want you?

Well, then.

You wouldn’t think a simple thing like not acting on an inappropriate attraction would be a personal triumph, but it is. Those moments, eh, that only you know are so difficult. The leaner diet Dr. Merrick suggested means that the moment she and Derek just had could be cherished for the rest of her life. It’s true they’re better suited to each other than to the partners they’ve been with, but maybe it’s impossible to abandon a marriage once there are children. It will stalk you one way or another. She’s not going to crow about it to the doctor either. He’d talked about private sorrows. Well, this can be a private joy.

46.

Lily arrives at the dancehall to find Gwen sanding the walls of the concession stand counter. Where’s Annabelle? she asks.

In town with Derek.

What’s she doing over there?

It was Derek’s decision, Gwen says. This is between you two, not me. I wish you’d figure it out.

Have you told Jenny and Maya they’re not going back to San Francisco? says Lily.

Never mind what’s going on with me, Lil. What kind of a setup is going on with you? I mean who’s minding the store?

We’re all minding the store. That’s what community is about.

Dream on. It’s so obvious about Annabelle. I mean it really is.

She’s going to have two fathers.

Even if Derek’s doing all the fathering? Don’t talk to me about my children’s confusion when you’re being so wrong-headed about Billy. He had the nerve to show up here and say he was taking Annabelle overnight, that’s why Derek took her to town. Look at the position you left me in.

You get yourself so cranked up about this, Gwen. You’re so tense about it. I don’t think it’s good for Annabelle to be around you. Maybe we can do some co-counseling on it, all three of her parents.

I don’t think Derek wants that, Gwen says carefully.

So he’s talking to you now, is he?

You do know that Billy tormented the life out of our brother? I don’t trust him one bit. He drinks too much for one thing. He’s mellowed a little, but you never know what he’s going to get up to.

Annabelle does him good, says Lily. And George has been like a grandfather to me. I have no intention of leaving either of them out of the picture.

A few days later, Gwen tells Dr. Merrick that the complications at Scarborough are getting too much for her. If he notices the projection split, he doesn’t say anything, maybe because he sees she’s figured it out for herself. He does ask her if she’s noticed that it’s when her self-respect gets deflated that she idealizes people. How’s your mother? he says.

We can forget about her.

We can’t actually.

She shifts and wonders if to him she’s in shadow. Doing far more than her share actually, she says.

It’s too bad there isn’t somewhere else on the island you could go, seeing the girls are settled there.

Well, she says. There’s the cottage.

What cottage is that?

We have a family cottage in Snug Cove

He looks at her astonished. You mean to tell me you’ve been coming here all this time and haven’t told me you have a family place over there besides that other place whatever it’s called?

I can’t go there. It’s closed down. The water’s turned off.

Well turn it on.

It’s not our time.

Whose time is it?

Isabelle’s.

They look at each other. The one time I saw your mother? I’ve never seen anyone with such a rigid but fragile construct. And I see a lot of people.

Who’s Isabelle?

My aunt.

Is she there?

She doesn’t go up. She lives in Birch Bay in the States. With her husband. She and my Mom and Aunt Evvie do a time-share. I haven’t seen her for years. We don’t see her.

Why?

I don’t know. She doesn’t want anyone there.

How do you know that?

My mom.

Your mother’s trying to be loyal to her family of origin, it looks like. What would happen if you went anyway?

I’m more afraid to do that than I was to go to the hospital to have the children.

That bad, eh?

He scribbles a few notes on a pad. You have to go, he says.

A few days later, Billy saunters into the daycare and stands watching Annabelle playing jacks on the edge of the old stage. Lily told you it’s okay if I take her overnight, right? he says to Gwen.

Right.

When he tries to pick her up, big girl that she is, Annabelle turns stiff as a board and begins to cry.

Worse, when Gwen goes to the store and sees the communal truck coming up the road with Billy driving, Annabelle is sitting like an iron rod in the seat beside him. Derek’s outside the post office checking his mail. When he sees the truck, the lines from his nostrils down the sides of his moustache deepen and his face collapses. When he sees Gwen, he looks momentarily comforted, then wrenches his face away.

That afternoon, Gwen finds herself standing on the resting rock, thinking about the way you’re supposed to point your skis straight down the hill instead of hanging onto the side of the mountain. Their cottage at the end of the point looks frozen; when she finally makes it down the hill, the walls seem miserably thin. The light switches don’t work, maybe there’s no hydro. She’ll have to light a candle when it gets dark, shade it with her palm so no one will know she’s there.

In the living room, magazines are piled neatly on the chairs so people won’t sit on them. A scroll with the moon painted on it is laid out on a card table. A few pieces of porcelain dinnerware with a bird of paradise pattern. It’s not a house, it’s a memorial. But to what? The telephone rings and she jumps. Maybe a neighbour has called her mother to say a stranger’s broken in. She finds a piece of paper and draws a diagram of the way the wood is arranged in the wood box, makes a few notes about the position of the pile of ashes in the fireplace so she can recreate the layout when she leaves. In the front bedroom, the mattress is covered with an old chenille bedspread, the top edge turned back diagonally as if waiting for a guest. It’s raining again; the damp air chills through the cedars. She manages to get a fire going by blowing through a hollow brass stick, picks pieces of ash from her lips. The first couple of times she tries to light the gas furnace, the flame goes out when she releases the pilot light. The third t

ime it works.

She dozes off in Grandpa Gallagher’s old chair in front of the fireplace. Dreams she’s on a ladder in the dancehall, trying to tie a rope around a tarp she’s flung over the pillars, manages to get it stretched over the thumb and first two fingers, but it’s windy and there isn’t enough fabric for the third. A bat darts into her sleeping bag; she jumps both hands on it like a cat after a mouse. A thudding that sounds like a body being dragged along the side of the house wakes her up from her nap. She leaps to attention beside the shaking gas furnace. A new voice—her own—replaces the doctor’s for the first time. Listen to it. Really listen to it. Maybe the furnace can’t function properly on high. Maybe it would do better on medium.

So this is what they call a therapeutic moment, lying on your stomach on a cold linoleum floor in a deserted cabin, scraping cobwebs with a flashlight so you can read a scummy dial. When she slowly turns the dial to medium, the furnace settles down. Percy is not standing above her with his hand raised. Neither is Grandpa Gallagher. Everything’s not going to blow up because she’s there. She’s there with whoever is waiting for someone who’s supposed to be there and isn’t.

Maybe she’ll bring all three girls over one day soon and spend the night since the furnace is humming along so nicely. It looks as if someone’s loosened the fuses so there wouldn’t be a fire. She tightens them, and the switches work. Yay. Brings her journal up to date, washes the dishes in the old chipped dishpan and goes down to reacquaint herself with Miss Fenn’s Rocky.

47.

When she returns to Scarborough, fork and shovel handles stick out of the ground with no one attached to them. Derek’s toque hangs on a wheelbarrow handle, one of his shirts spread out on a lilac bush as if to dry. It’s raining so hard she stumbles and slips on a bunch of apples spilled from a box. Why’s the bathtub pushed over? Inside the house, there’s a miserable empty feeling, as if someone she doesn’t care about is sick. The clock ticks. She calls; no answer. No one’s in the shed, no one up in the pens. Climbing up through the orchard, she sees Derek’s chainsaw stuck into the ground outside the barn door. Enabler, someone hissed the morning she held him in the group room. Inside, the large barn walls vault into a wide roof with a loft. Below it, Derek’s feet are swinging back and forth like a pendulum. When she sees him, her own feet jump off the floor with shock. Maybe he was leaping from the loft and miscalculated; she rushes over and tries to push a bale of hay under him, but above her, his head lolls to the side, squeezed through the noose as if his neck had been wrung. The rest of him points straight down. When she climbs up to chop the rope and he tumbles down, she tries to breathe into him, but his lips won’t stay open. Hooking his dental partial out like a wishbone, she tries to spread his mouth with her thumb and middle finger, but it won’t stay. Flipping him over, she straddles his back, presses and releases with her palms as if he’d drowned. Turns him face front, pushes hard on his chest. Nothing. Don’t let this be happening. Hauls him up, leans his back against her chest, tucks her knees around his hips. But he won’t come back, he won’t ever come back, and down at the house, the truck’s pulling into the driveway.

Are you all right, Gwen? You don’t look too good, Billy says, standing by the truck holding Annabelle’s hand. She didn’t want to stay overnight this time. I’ve brought her back. The girl’s stricken eyes follow the line of Derek’s markers up through the orchard as if she knew something terrible would happen if she was ever in the truck when Will was driving instead of Derek. When Roxy jumps up on her, instead of telling her to get down, she takes her paws and walks her stiffly into the house. Gwen phones Lily who’s visiting a friend. You need to come home, Lily. Right away.

Are the children okay?

Yes, but you need to come home. I’ll tell you when you get here.

What have I done? says Lily at the door.

You haven’t done anything.

When the school bus arrives, Jenny and Maya charge in, smash the fridge door open, smear peanut butter on bread.

I need to talk to you, Lil. Gwen takes her sister’s arm into the living room, closes the door. Sit down, she says.

Lily does.

It’s Derek. It’s terrible, it’s so terrible, but he’s dead. He hung himself in the barn.

Oh, God. No. Lily shakes her head over and over again. It can’t be true. Is he still…?

Up there, yes. I tried everything. She starts to cry.

I have to go to him.

Rushing past the children up through the orchard, she disappears into the barn. Gwen stays in the living room staring at the wall, then Lily’s back at the picnic table, lips and eyes tight and thin. I can’t believe this. What are we going to tell the children? she says when Gwen comes out.

It’s too late to tell them anything tonight, Gwen says. Let’s get them to bed. If you take a step back, you’ll fall off the loft. I called the police and the coroner when you were in the barn.

Annabelle comes out and leans into her mother’s side. Lily stretches out her daughter’s arm, touches the Band-Aid. What’s this?

It’s an owie.

An owie. You’re too big a girl to say that. Lily looks up at her sister. It looks like she’s had some kind of a needle.

Has she had all her vaccinations? says Gwen. Billy wouldn’t have taken her for a booster?

Of course she has. Derek took care of that. Where did this owie come from, Annabelle?

Annabelle doesn’t answer.

When the police and coroner arrive, Gwen heads them off at the driveway, herds them up the hill.

When she and Lily tell the children the next day, Jenny starts picking at her fingernails, alarmingly mature as she tells Maya and Annabelle it’s like the time they found the dead bird in the garden and buried it in the lane. We’ll have to bury him, Jenny says. In the living room, she lies on the sofa with her head on her mother’s knee, wanting to have her hair stroked back over and over again. Poor Derek, says Jenny as if he were a whippoorwill.

The place feels bereft of him, littered with unfinished jobs, his outline standing at the ready. Lily keeps telling the kids things they already know. When Jenny takes leftover porridge out to feed the dogs, her aunt informs her she should put the porridge in the dish, not give it to the dog in the pot.

I know that, says Jenny.

Annabelle stops talking. She doesn’t open her mouth except to eat. When they ask her about the owie again, she tightens her lips and turns her head from side to side.

He wouldn’t have taken her for a blood test thinking of a paternity suit or something? Gwen says.

Would he have, without saying anything to me? says Lily.

I don’t know.

Now it’s Lily’s turn to wander around, staring at the places she and Derek had been together as if it’s taken this unerring silence for her to know how unhappy he was. She goes around picking up after him. At least she’s stopped in her tracks for once. She has to call Derek’s parents in England, and that’s just awful. She puts down the phone. They said they’re going to come over to see Annabelle. I didn’t know what to say.

Well, what are you going to say?

I don’t know.

The adage about the children in your neighbourhood being everyone’s children Gwen kept touting to Eugene? If you ever find yourself trying to live in that never-never land, he said, count me out.

Three-way Split

48.

August, 1975

Isabelle? This is Gwen.

Gwen. How good to hear your voice. Where are you?

I’ve been spending time at the cottage actually.

I’ve phoned a few times. I had the feeling someone was there.

So it was you calling. I was wondering if I could come and see you?

Of course you can come and see me.

I was thinking of tomorrow.

Tomorrow it is. Will you come on the bus?

I’ll come on the bus.

I’ll meet you at the station in Blaine

/> And there she is, still tall and gaunt as a heron, her long neck creviced as if by a potter’s thumbs. Dressed thinly in gabardine slacks and a fake leather jacket, her protruding eyes look watery, but she still has that amused ironic smile playing around her mouth as if she’ll always find life strange and amusing. It’s been a freak spring, yesterday cold as winter; today the sun’s melting the tarred centre line. They climb into her old Pontiac, find themselves held up by a circus parade of all things.

Everyone’s been looking forward to having a parade with an elephant in it, Isabelle says. An official stops the car, leans in the window. It’s the elephants, he says. They’re being watered. It’s such a hot day the pavement is hurting their feet. We’re going to hose the streets down now.

Isabelle’s smile shows a couple of gold-rimmed teeth. She lifts her rhinestone-cornered glasses from her face, dabs at her eyes with a hanky. Laughs in that old way of not caring whether anyone’s going to join in. They could have made shoes for them out of cardboard, she says. How’s your mother?

Fine. She has her gardening, and she’s learned to fly.

No.

It’s true. The planes she and dad fly are too small to take any luggage. When they go anywhere, she has to wear the same outfit the whole time. She has one sleeveless dress, wears a Viyella blouse under it if it’s cool.

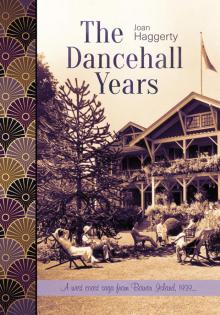

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years