- Home

- Joan Haggerty

The Dancehall Years Page 24

The Dancehall Years Read online

Page 24

I believe that and look where it’s got you.

At least, she manages to consider the doctor’s unspoken point that she’s at liberty to say she’s not up for this approach, in which case he would probably refer her. I’m sorry that psychology falls into jargon so quickly, he says, as if he’s about to pronounce relationships the way Jenny would later in a snide parody of anything psychological. An ironic smile cuts briefly across his neither open nor closed face. There are other rewards, he says.

Already, she’s curious as to what those might be. Slowly, as she gets physically stronger, she’s more able to concentrate, but the more she refuses to let herself call Eugene, the weepier she gets. Sometimes at night, she makes babysitting arrangements, gets in the car, heads down to a dancehall in Point Roberts, dances blindly with whomever she picks up, heads back to strange motels.

It’s a bit self-indulgent, isn’t it? the doctor says when she tells him.

You want me to be totally celibate? she says. I don’t know if I can do that.

Slave, he says.

What did they do before Oshkosh overalls anyway? You’ve got your striped pair, your worn jean pair. Annabelle’s turned three and is growing out of the last pair. Maybe she should mount them, gild them like baby shoes. Tries to understand that throwing a fit about wanting to play with the yellow truck is a way of insisting on your right to be yourself. If somebody’s got something of yours, use your words. You need to look for your hat. It’s where you aren’t. Keep your leg to your own body please.

At Blenheim St., when they’re visiting, Grandpa makes breakfast and asks Maya what she’d like. I’d just like a little breakfast, she says. When she comes to the table, he presents her with a crouton on a plate, a thimbleful of orange juice, and a doll’s dish with a piece of scrambled egg and a crumb of bacon. Funny Grandpa. At supper, Jenny reads them a write-up on the planets she’s doing for school. If Earth’s a grape seed, Jupiter would be an orange. The sun is several watermelons. Percy takes an orange from the fruit bowl and places it near the ketchup bottle. Don’t put it on the bird’s face, Maya cries. You’ll get it in its eye. It won’t be able to fly out in the planets where it wants to go. See, it’s here. And it was, patterned in the grain of the table.

A few days later, Ada unties her apron in the middle of a thunderstorm, plucks her cardigan from a hook, walks down to the low corner of the lot where she used to be able to see the Fraser, but the cedar has grown so high she no longer has a view. Arrows of lightning jag across the sky. Gwen wants to call her in, but her shoulders are set against being disturbed.

I don’t think I’m afraid after all, she says when she comes back.

Of what, Mother? Gwen’s so astonished by the flood of warm pleasure that the raised blind over her mother’s face gives her—your mother’s not what you’d call accessible, is she?—she steps up close, not in her arms exactly, but not that far away either. Her mother reaches up for her glasses, but her fingers pinch the corners of her eyes because she’s already taken them off.

Embrace your fears, Gwen, she says.

All of them?

Don’t make any appointments for Wednesday afternoons. I go out Wednesday afternoons.

Where, Gwen wants to say, but doesn’t.

Eugene calls to see what Jenny wants for her birthday.

A sheep for my bed, I guess.

When his gift arrives, it’s a length of brightly patterned cloth. Orange and yellow tigers skulk in a dark green jungle. He’d thought she said a sheet for her bed.

Oh dear.

Dr. Merrick’s office is low-lit; he wears tweed jackets and sober colours. What are you doing for bucks? he asks.

It’s a problem.

What about formalizing the child support?

I can’t talk to him, she says. I’ve said it and said it. Knowing a cheque’s going to be there at the beginning of the month is more important than the amount. I don’t know why he doesn’t send me post-dated cheques.

Have his salary garnisheed.

It’s not reciprocal between here and the States. I can’t work fulltime with the girls so young, and with no father, they need more of me, not less.

He should be coming forward with the money, says the doctor. It should be at least $600 a month. Get a lawyer.

They’ll make me take the children back. They were born there. He’ll get a lawyer who’ll make me do that. Why does he do this?

Control?

Why would he bother? He doesn’t want me.

I’m not talking about you.

He kindly doesn’t say for once.

Part of it was my fault too. I couldn’t adjust, and in the end, I couldn’t even do the basics, I was feeling so terrible.

I know that, lassie.

Your problem, he says, is that you let need interfere with judgment. You distort situations for the sake of gratification. When I asked if there was still anything between you and Eugene, besides the children, when you said yes, it was a knee jerk reaction. You didn’t ask yourself why’s he asking me that question. It’s the same impulse that makes you act out sexually. The trouble with school for someone like you was that it was a ball. You didn’t learn to tolerate frustration.

Really? says Gwen. Sex is so bonding. Did you learn that at your father’s knee? That love and sex are dangerous.

Yes, I did. I’m not trying to take the agony out of your life, you do realize that? So you’re uncomfortable, he says looking discreetly at his desk top. No one ever died of it. I guess you’re going to have to get used to a leaner diet.

How long am I supposed to go on like this, keeping the brakes on? she says. Are we nearly done?

It’s good you feel like that, but no. Channeling it would be another possibility. It’s an age-old technique, after all. Instead of sexualizing your energy, why don’t you use it to write down some of your early memories? As I said, it shouldn’t be this bad, your having to separate. It’s a loss. You’re worried about the consequences for the girls. But you go on feeling that he’s you, walking around down there. Why is that? That time he came up to see the children? Should you have had him stay with you? Isn’t that what hotels are for?

He’s my children’s father.

Still. It doesn’t have to work, you know. You can’t always make things work by putting energy into them.

When he comes up here…

I know. Nothing goes right. It’s the irresistible force and the immovable object all over again, but if you learn to tolerate the frustration, a space of regard and self-respect will begin to open in many aspects of your life.

A few months later, on Percy’s birthday at Blenheim St., there’s an envelope with his name on it propped against his glass. As a joke, he holds it up to the light to see if there’s a cheque inside. Unbelievably, it turns out to be a pilot’s license made out to Ada Killam. He replaces it, hurt and insulted.

This is not funny, Ada.

It’s not a joke.

Everyone’s forks are halfway to their mouths, profiles whapped to Ada’s end of the table.

I’ve been taking lessons. I got my license.

Percy’s face is going to fall on the table if someone doesn’t catch it.

You have to put a plane in free fall to get a pilot’s license.

I did that.

Ada gets up and comes back with the car keys in her hand. Let’s go.

Where?

For a ride in an airplane.

I can’t believe this.

Percy looks at all of them as if to say, you’ve witnessed this. Don’t ever forget it. As if they could. I had to, Ada said later. Dad was so unhappy.

Children and grandchildren are waiting when Ada and Percy return, Jenny perched on the bottom stair as if the doors to Christmas haven’t been opened yet. Percy is radiant. Would you believe my wife, you children? Now I’ll be able to fly again because there’ll be another qualified pilot at the dual controls.

44.

Imagine my mother doing that,

Gwen says to Dr. Merrick. I didn’t know she had anything like that kind of courage.

You must be proud of her.

I am.

He smiles gently, letting the atmosphere settle. His consistent reliable presence sends a message that, with time, hard work and a touch of grace, the patient might at last begin to integrate the fragments of her life. When she feels emotionally drawn into a situation, he says, she might try taking a step back and asking who is this person, what is he or she about? It takes a lot of practice, but it’s worth a try. That way you widen the space where you can look at situations clearly. It’s as if he has to take the chance of entering the place in her psyche where she’s loneliest, without giving her the wrong idea. Any indelicate gesture would provide an inappropriate crutch, and she’d be back to square one. It’s as if he knows she has to conserve her energy for an ordeal they haven’t discovered yet.

I miss the closeness, she says.

Of course you do.

It’s so lonely. Is this it then, is this forever?

The compensation for that is supposed to be a growing sense of inner strength.

Oh, she says sadly. When’s that supposed to start?

When she goes to put on her coat hanging by one of the bookcases, she sees a clear bottle of sea stones filled with water on the green carpet. Has that been there the whole time? she asks.

The whole time.

Why are you smiling?

Because you’re smiling.

He says he brought the bottle over for the architects when they were building the hospital. He wanted the walls and floor to be the colours of stones under water.

You did a great job. This room is an oasis.

Good. You don’t like things to change much, do you?

No, I like them to stay the same.

She thought he’d smiled because he was amused, but walking back to the car, she realizes it’s important not to mistake analysis for social conversation. He always has a reason for what he says and does. That night, she looks at a love poem of Eugene’s she’d found in the apartment and brought with her as a keepsake. Now, reading it in the driver’s seat, she realizes it had been written to somebody else.

A few days later, a ruckus starts up in the yard where Jenny and Annabelle are in the bath. They’ve been told the bath water’s only for rinsing, not soaping, but a shivering Annabelle stands in the tub sluicing bubbles from her narrow body. Jenny’s nonchalantly soaping herself, one knee over the other like Bugs Bunny on the lam. Tell Annabelle that Kayak Will’s her Dad, she says. Everybody at school says so.

Derek’s her main Dad, Jen, Gwen says picking up a facecloth and wiping her niece’s face. You girls know there’s not supposed to be soap in this bathtub.

He’s not my maindajen, Annabelle cries, flailing in the towel as if it’s a straitjacket. He’s my Dad.

Yes, honey, he’s your Dad.

A Soft No

45.

March, 1975

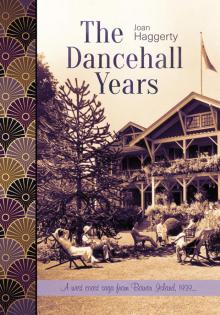

Neither Gwen nor Derek will remember who first came up with the idea of restoring the dancehall. Maybe the pavilion itself called out to them, empty and unused as it’s been all these years. Moss coats the roof, the central columns are covered in mildew, and the walls are so damp they’re about to collapse into the forest floor. The two of them decide that, if they prepare a strong enough application, they might be able to persuade the organizers of Habitat Forum in Vancouver to feature the Bowen pavilion as a recycled heritage building. People could take an excursion to the island and have a look-see. Recycle the hall into a community centre after the conference maybe.

Don’t let them touch the dancehall floor, Ada says when she hears about the project.

When the grant comes through, Derek manages to get his hands on a portable sawmill, which they erect in a covered picnic table area that hasn’t been torn down yet. A beachcombing gopher opens its claws on Miss Fenn’s Rocky, lifts logs to drag to the dancehall to replace the moldering Corinthian columns. Peeled and varnished, they’ll be erected in the centre of the hall before the originals are removed. Horizontal beams lie on the floor ready to lift into place to form the new centre octagon.

The concession stand area of the pavilion has been set aside as a childcare centre: the plan is to exchange the special dancehall window for a door so the daycare can have its own access. Gwen’s strip ping recycled wainscoting when Jenny shows up cranky because she had to stay behind after school and clean out her desk.

They’d better not take Will’s log, she says, looking at the logs on the floor.

Billy doesn’t really live in a log, Jen. It’s just a way of speaking.

When he came in to help earlier, Billy Will crossed the hall to the special window where a huckleberry bush and a thin cedar grow from the old stump. Opens a beer on the old concession stand bottle opener mounted on the counter.

I’d like to have Annabelle overnight soon, Gwen. Lily and I agreed on that before she left.

She didn’t say anything to me, says Gwen.

I do have some rights here, he says more humbly than she ever thought possible.

It’s up to Derek, Gwen says. But he’s in town.

At Jericho Beach in Vancouver, where the Habitat Forum conference is to be held, the plan is to build seats in the hangars that housed the planes that patrolled the coast during the war. The results could be monitored over the years for shrinking and duration. Plus, everyone’s getting paid, which is very cool. Jobs for people coming out their ears, Derek tells the crowd at the pub when he gets back from the mainland. Including me, part-time.

He draws a picture for the girls of the west gate logs they’re going to insert into one another in the shape of a Ferris wheel. A forklift will deposit a huge piece of driftwood to be carved into a whale. It should be called a lifting fork, Jenny says. Is there going to be stuff for kids?

Sure, there’s going to be stuff for kids.

An unseasonable gale blows straight off the Sound, and the wind roars through the huge doorways in the old airplane hangars, freezing the Jericho crew. Derek comes home cold and wet.

Lily told Billy he could have Annabelle overnight, Gwen says when he comes in. I’ve held him off so far but…

Absolutely not. I’ll take her to town with me if he’s bothering you. How’re things at the hall?

Okay. It feels like we’ll be sanding forever though. We don’t mind the seating being rough, but not splintery, right?

Right.

At least she’s starting to pay better attention on the home front, noticing the way Derek spends more and more time wandering around the place, half-heartedly pulling deadhead from the bush and leaving it to chop for firewood but never getting back to it. Cooking Brussels sprouts, he moans there’s no reason they have to take so long. When she suggests a lid, it seems like the end of the world when he can’t find it. We had a wok lid. Working on the truck or raking the garden, it’s as if the position he’s standing in refuses to jibe with the position he’s used to standing in. She checks these observations off like the numbers the doctor gets her to add up to help mobilize her matter-of-fact side, which got obliterated in the course of her growing up. Maybe you were stopped mid-action so many times, it was difficult for you to figure out how you wanted to do things, he says.

Sometimes I was hit, she says. Why do women always do things the hard way? How can you be so stupid? Percy yelled when she tried to wind the hose on her arm instead of using the curved rack nailed to the wall. And she froze.

Leo was the one who was good with numbers, so I wasn’t supposed to be, she says.

I understand that, but you need a matter-of-fact side to develop a self-observing ego, he tells her. A person usually acquires one by hearing the adults make empathetic matter-of-fact observations. You handled that well. What would your options be, do you suppose?

What’s a self-observing ego?

The part of a person that’s looking down and observing the whole circus.

I didn’t hear much in the way of

that kind of voice, she says. My mother was busy. She did her best.

I’m not saying she didn’t. Maybe you didn’t like the way they handled you. What’s Derek doing do you suppose? Dr. Merrick asks when she tells him about the way he’s wandering aimlessly around Scarborough. Her blank look says beats me. Looking for himself? he asks.

Later, she lies awake in the bunkhouse, staring at the ceiling, wondering why putting herself forward to support Derek starts up her own physical yearning. If burning down there is a symptom of being separated from a part of herself that never grew, maybe it’s true, as Dr. Merrick says, that all her “love” relationships so far have been narcissistic. Maybe if she ignores being aroused, it’ll die down.

Where’s the turning point in all this? How long is she going to go on rotating in space, as Dr. Merrick puts it? How long will he have to model matter-of-fact behaviour before she gains some traction?

Do you have any idea how difficult this is? she asks.

I do, he says gently, and takes off his glasses, which he never does. For a moment, it seems that his soul steps across his desk and touches hers. The winter tide finally rises high enough to reach the driest place on the beach.

After that, she begins to see her projections slide up the body of the person she’s idealizing, the way paper outfits slipped up over her cardboard dolls. You idealize everybody, he’d said. The way, when anyone criticizes her, her self-respect is given over to whomever she imagines never makes mistakes. Could she permit herself the hope that Dr. Merrick trusts her a little to risk reaching out to her with nothing but his soul? That wasn’t projection. She loves him when she thinks about it—she does too—but is she partly loving the fact that she feels seen and heard by him? That he treats her with respect and her mother doesn’t?

If no one acknowledges your secrets as a child, it makes sense that part of you ends up sitting beside yourself feeling abandoned, Dr. Merrick says on her next visit. Maybe she’s projected that lost part of herself onto the men she’s known and expected them to embody it. She’ll think about that. They look up phone numbers. They call mechanics. They call lawyers. The desert of celibacy exhausts her, but he keeps repeating that sexual resistance is the best place for her to practise tolerating frustration so her matter-of-fact side can develop. Even when she feels as if she’s about to smash herself into the wall of his office, she knows he’ll stay with her no matter what. Knowing he’s there makes all the difference. I’m trying to get you to care about you, he says. There are places she can feel they’re skipping; places they look in but can’t see anything, even though he keeps going back, asking the same questions. Straight from preteen to her disguise as an adult? That pretty well says it. The unidentified pain they’re not going near as long as her daily reality is difficult stays in place like a bookmark.

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years