- Home

- Joan Haggerty

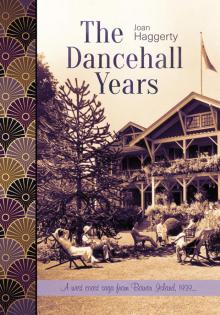

The Dancehall Years Page 11

The Dancehall Years Read online

Page 11

Dr. Stan’s face is sad when he looks around as if he has no idea where he is. Then he shakes his head, and his face clears up. His hair rises straight off his head for an inch and kinks into the air. The smell of a good-looking man coming fresh from the outside makes Mother turn her chest up to him like an offered tray. The dentist gives you a plaster turtle after he’s finished your filling, but when Dr. Stan’s looking after you and you feel like you’re going to cry, he stops whatever he’s doing, makes a poker face, raises two arms straight to one side and breaks into a tap dance. His legs hang loose like a puppet’s. At supper when he’s asked to stay, he does something secret to the ketchup bottle. Give it a twist, a flick of the wrist, that’s what the showman said. Halfway through supper, the lid pops off. Fairies, I guess, he says and winks.

In the attic, Leo’s hunched against the sloped ceiling of his room. When Dr. Stan takes the book from the chair so he can sit on it, Leo’s eyes follow the book so he won’t lose his place. The doctor looms above him like the giant with his hen. Asks for a soup spoon to warm baby oil over a lit candle. Before we do this drill with the spoon, son, I’d like you to stand up, lean over and kick your opposite foot. Harder. Is it out?

I don’t have water in my ear, it just aches, Leo says.

Dr. Stan’s head pushes against the ceiling and beans grow from his ears. Back in bed then, he says. Down on your side. He holds the warmed silver spoon carefully like he’s in the egg-and-spoon race. Is it like cod liver oil? I don’t like cod liver oil.

I’m going to put it in your ear, son, not your mouth. A warm rush and it’s in. Sleep on that side, he says. Things will seem better in the morning.

But they don’t. They never do any more. Maybe if she’d won that sandcastle prize which she should have, Auntie would have had enough money, and the two of them would be having a lovely time over at Scarborough, waiting for her friends to come back from whatever other camp it is they’ve gone to.

If I’ve told you once, Ada, I’ve told you a thousand times. It’s going to be a lovely sing-song and bonfire at Scarborough beach. It’s an adventure for the kids. They’re going to have Evelyn in one boat, Dr. Stanley in the other and somebody else’s sister or cousin or aunt in a third. For heaven’s sake, the kids are fine. They’re having a wonderful time. What are summers for?

Anchors aweigh, Aunt Evvie says, lifting the sailor hat off Dr. Stan’s head and putting it on her own. Loading the children into the putt-putts at the motorboat rental, the two of them act like they have to know what other people are going to say before they say it so they can go on laughing. What is it with you two, did you see a stranger across a crowded tennis court? Love at first dribble? The next inboard is off, motor ticking hardity har har. No fooling around back there. Gwenny-Henny can come in our boat, Billy Fenn says. Nothing to do but try Leo’s trick of finding a distant star that might be like their own sun with a planet that has a girl like herself on a putt-putt heading into a dark lonely sea. You tell us if there are any logs coming up, Gwenny-Henny, Billy says. My Bonnie lies over the ocean, my Bonnie lies over the sea. We don’t want to mess up the ocean so someone please bring me a pail. They pass the spot where she swam her Juniors test, the wave in front of her so high it was like swimming over a wall, the sea so rough her teacher let her dog-paddle the last few yards instead of crawl. When she climbed onto the hotel wharf, her mother dried her as if she’d never seen her before in her life. I couldn’t believe they didn’t cancel, she heard her say up through the chimney gap. She was so brave out there.

At least when she swam the Juniors test she was in charge of her own body, not like now with Billy thumbing the lever to slow the boat, then pushing one of the oars between his legs. What we’re going to do now, Gwenny-Henny, is tell rude jokes. Boy, are you ever going to like what we’ve got to show you. In case you don’t know, this is how you got born. Your dad put his long one into your mother’s hairy one and spurted, and you got born. Yep, they got fooling around when no one was looking, and you popped out of your mother’s pee hole. Gwen huddles on the putt-putt floor, arms around her knees. At least the things he says are so dumb you don’t have to even pretend to listen. As if her parents would do something like that. It would be out of their range, like a foreign language.

If your date’s ever driving badly, her dad will say later, or misbehaving in any way whatsoever, you say stop the car. Get out and use your mad money to phone me to come and get you. In the middle of Deep Bay? Watch out for Miss Fenn’s island! The tide’s so high Billy might not see the rocks.

When the putt-putt rounds the Millers Landing corner, the waves slap the pebbles so hard the bow scrapes the edge of the rasping beach. After they land and climb out, Dr. Stan holds up his hand to stop them so they’ll turn around and go back along the beach the way they came. Don’t look back, he says and the kids obey. Except Gwen who looks anyway and sees Grandpa Lyndon and Grandma Flora crouched beside the bloated deer carcass with its face all nibbled away. Sea wrack twists in its antlers; its legs are so stiff it should be carried upside down, hooves lashed by thongs to a stick.

When the bonfire’s lit, the kids are told to peel sticks for the wiener roast. Dr. Stan’s supposed to be organizing the singsong, but instead of giving them a note, he decides to walk down to the water and stare hard at the shoreline. None of the other grown-ups are doing what they’re meant to either; they’re back in the shadows, acting as if they’re going to start yowling like the cats you hear but don’t want to hear in the bushes on dance nights. Go back to sleep, it’s only the dance, the grown-ups call from downstairs. A couple of them lurch over each other as if they want to turn themselves inside out. When Evvie and Dr. Stan come back to the fire, Evvie’s got her arm around Dr. Stan, instead of his arm around her; his head is down on her shoulder as well, so things are the other way around from the way they’re supposed to be again. Buckling over with dry heaving, he leans over like he’s trying to throw up but nothing comes out. Parts of his body look stiff in the firelight, as if he’d been put into an icebox by mistake, taken out barely in time, and they had to stick the frozen parts of his body back together. The wind comes up, and pebbles scrape the steep beach as he clings grimly to Evvie, who tries to unfasten him limb by limb, but every time she removes a hand, he gloms it back on. When his fake hand starts clawing at her, she looks alarmed, as if she’s afraid people will see her trying to unfasten a large crab stuck on her chest. Finally, she manages to drape a blanket around his shoulders and get a Thermos into his hand.

It’s the gravel, he says. I can still hear that scraping. There were parts of bodies all over the water. It was Dieppe. Trying to find my own hand. I couldn’t find my own hand.

A couple of other grown-ups try to get the singing going, but nobody believes in it; it sounds hollow the way it does at school when you don’t have a good music teacher but have to try anyway. Stuck out in the middle of the night with nobody’s marshmallows turning golden, people poke their branches into the fire, torch the white puffs until the black mash fastens onto the sticks. Waves grate the beach, scrunching into the ocean, as the kids break into small groups and huddle together.

Billy disappears up the pathway, comes back to the fire looking tired. Maybe he’s only mean during the day. Maybe he’s nicer at night the way their toys in the attic might wake up and talk softly when the children are asleep. Nobody’s supposed to be in that goddam house, he mutters in a deep voice as he hunkers in the sand, his face swelling like a potato in a bonfire. When he takes off his shirt, he’s bright in the moonless night. Firelight picks out red cuts on his thin back. How am I supposed to find that money, he says. With those new people living there, eh? Can you figure it out, Gwenny-Henny? He drinks a gulp of pop, heads up the path toward the farmhouse.

No point saying you’re going to be brave unless you are, so she follows him. Watches his arm whip out from behind a cedar to hurl a rock. What’s the big idea out there? Grandma Flora hollers. Come out where I can see you. Grandpa

Lyndon’s huddled in a chair in the open doorway, looking so helpless he could be in diapers. Someone should tell Grandma Flora that no one here wears those worn out print dresses; men don’t wear worn-out suits and shirts with frayed collars either.

In the cedar grove, she finds Billy sitting on the ground leaning against a tree. That’s supposed to be my dad’s house, he says, jerking his thumb. My grandfather gave the farm away, and now my father has nothing. The Jap who got it was saving money to make it up to my dad, but he got taken away before he could tell him where it is. My dad says I have to find it. What’ve you got there, Gwenny-Henny?

It’s some money, Billy, she says rushing the idea out. I’ll give you all of it if you’ll leave my brother alone. I’ll look for the hiding spot when I’m over here. I’ll do it, Billy, I promise. He counts the coins. Okay, Gwenny-Henny. It’ll do for starters, but I’ll be watching you.

Back at the beach, she wants to wrap her arms around Aunt Evvie’s waist and tell her what she’s got herself into, but she knows enough to stay quiet the way Mr. Yoshito says that there has to be quiet around seeds once they’re planted so they’ll grow.

No, Gwen, you can’t come back in our boat, Aunt Evvie says. I’m counting on you to be a hundred-percent grown-up tonight and help look after the younger kids. There’s not a single thing to worry about. Every boy in that boat has his Seniors.

In Kind

20.

The next day, the people in the mail queue wait for the wicket to open, and a pale Isabelle stands slotting letters into mailboxes as if there’s no tomorrow. In so thick with them Japs, George Fenn thinks, he wouldn’t put it past her to slip a few care packages up to the Slocan Valley or wherever it is they’ve got them penned. Couldn’t be getting enough sleep with those dark circles under her eyes. Maybe she knows where that money’s hidden. If they told anyone, it would’ve been her. He’s using his car as a taxi now; he’ll offer her a ride to the hotel. Plain woman like her, she’ll be flattered to have his escort service. Crying shame the hotel flower gardens are going downhill, he’ll say to get things started. The place isn’t the same without what’s-their-names.

When Isabelle rushes past him without acknowledging his signal, Lyndon Killam is sitting on the bench under the overhang outside the store as the rain pours down in sheets. He stares blankly down the side of his beaky nose, pulls out his wallet, and hands George the new address card Percy’d written for him. Doesn’t see, doesn’t hear, that one, George says to Lyndon, nodding in Isabelle’s direction. He’s growing a paunch, has to lower his extra chin to read the Scarborough address. Six of one, half a dozen of the other, he thinks, taking Lyndon’s arm around to the passenger side of his truck.

At Scarborough, Flora’s on the back porch, staring in dismay at the overgrown yard. Her anxious look is so much like George’s mother’s when they came back after a winter in town, the years disappear, and for a moment, he feels she is his mother, the way her hand pushes her hair back as if wanting to clear a view to the ocean. She bends over a box, stands straight again. He seems to be shrinking Flora thinks, eyeing Lyndon in the cab. Thank you for bringing my husband home, Mr….?

Fenn, says George. George Fenn. I’m the Union caretaker.

Come in. I’ll give you the tour.

I know the place pretty well, he says. I grew up here.

Did you? she says. He might well have, everyone else seems to have. It’s so wet her visitor has to pour rain from the brim of his fedora. Inside, they hear a chortling in the basement. What is that? she says. It’s been irritating me all morning.

That’ll be the sump pump. Them things give up when they have a mind to, and then you have a flooded basement.

It’s been churning all night like an intermittent waterfall. Did they have one back home? She can’t remember. How can she be forgetting things in her own house? Lyndon’d thought the noise was a longed-for rain for his wheat crop. Sounds as if it’s raining at last, he’d said radiantly. The stalks will green up, you’ll see. Let him remember the good years before the drought and dust storms ruined their lives.

It was so hot and dry that fateful day Percival took their creeping daughter down to play in the cellar where it was cooler, the wind even layered dust in the basement. Dust on the vegetables if they’d been lying on the plates for five minutes. When the scarlet fever came and they had to burn the furniture, every stick went up in flames except for the one rug Lyndon threw down the cellar stairs.

She’d been looking for her photograph albums all morning, and when Mr. Fenn left—she’ll make a point of calling him Mr. Fenn, that way everything will be above-board—darned if they aren’t sitting on the counter in front of her. Whole sections where the pictures had been torn from their corners. She’s almost managed to keep the child out of her mind, announcing to Lyndon on the train that the mountains would be a wall between themselves and her grave. They’d buried her on the Prairies, and on the Prairies she would stay.

So why’s she having to walk around the kitchen shaking the album by its spine, pages flapping like wings, hoping the snapshots might be loose and fall out on the floor? Whoever would have taken them, she mourns, forgetting that in her grief she’d torn the images out herself. Maybe it was that young man who comes over here and throws rocks.

People say you shouldn’t retire to an unfamiliar place because it might be hard to make new friends. Maybe they should have thought about that before they left the Prairies. You can’t walk anywhere here without some branch poking you in the ear. You can’t tell clouds from sky. There’s no decent distance for the eye to travel, and where has the horizon got itself to? Is there a barn? Lyndon asked Percy when they arrived. There’s a barn. Are there cows?

You could buy one.

That’d be sufficient, he said with dignity. Terminal City all right. She wants to go home, drought or no drought. And that mail clerk, Percy’s sister-in-law, the one who looks like a widow even though she’s engaged? She’s tried to be friendly with her. Nothing for you, Mrs. Killam, she’d said coldly, as if the name meant nothing to her. Well, they’re not here for the social life.

Most mornings Lyndon gets up before her and takes off down the Government Road stopping at fern-infested cottages to ask how their cows are getting along. Sits forlornly on the bench outside the post office, watching people go in and out. The loneliest place you can be in this world is where the person you thought loved you doesn’t recognize you but still expects to be fed. She can’t let any of them know his condition or they’ll take him away. Best if she doesn’t encourage Gwendolyn to come over either, she’s far too observant.

If Eleanor were here, they’d know what to do. When she goes upstairs, she immediately spots the photograph of her sister tucked into her dresser mirror. Smack up in the front of the snapshot as if asking for someone to take her hand and help her out. Head down so people could see the appliqué roses stitched on top of her pillbox hat. If you’re short and people are obliged to look down on you, Eleanor liked to say, they might as well have something nice to see. If she hadn’t wanted to leave the nursing home, why had she stepped up so close to the camera? There’s supposed to be a decent residence at the end of the pathway behind her, but there’s only a shack. Cold wind blows between the wooden wall slats. No insulation. An iced-over pail of water hauled from a tap. People bent double tending to sugar beets in the yard.

What kind of shape’s the spare room linoleum in? Worn but clean. When she passes that bedroom above the kitchen, she always closes the door as if there’s a baby sleeping. Downstairs, crossing the well-trodden piece of floor from the stove to the sink, she suddenly feels as if she’s in the body of a much shorter woman hunched over in a sleeveless tunic.

Nothing to do but phone Percival again. Is it too much to ask, the occasional lift to the boat terminal? Eleanor’s not in a shack, Mother, he says. She’s in a nursing home in Regina with a starched nurse at her beck and call around the clock. Watercress sandwiches for lunch. I most certainly

will not arrange to have her put on the train. We are not having her come out. Hold on a minute, Mother. I know it’s your nickel. It was a mistake having you move over there. I’ll call you back. Don’t go anywhere.

As if she could. She’s been holding the phone at arm’s length for most of the conversation anyway so she doesn’t have to listen to the parts she doesn’t want to hear. They have their lives, she’ll grant you, but how long do you wait before it’s not too soon and call them again? Only ask about them. Otherwise you’ll sound like you’re pleading, and they’ll never call back. All she has to count on is some strange young fellow who throws stones from behind trees. And here’s Gwendolyn over for more corn. The other day, she’d caught her turning the clock over and shaking it like a piggy bank. She’d come into a room and find her lifting up a pillow. If only Eleanor were coming down to the house from her loft in the barn as usual. That room is supposed to be for the hired man, Lyndon would say when Eleanor came to the kitchen door asking for a bit of flour to use as white paint. Do you know what she used for black?! Percy’d thundered at his children at the dinner table, waving the carving knife. Prairie dirt! She started giving music lessons and let the children paint pansies on the dining room walls. Pansies on the walls, think of it.

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years