- Home

- Joan Haggerty

The Dancehall Years Page 10

The Dancehall Years Read online

Page 10

Ada’s rearranging pinecones around the holly centrepiece Percy’s office sent, as if she spent too much money on a hairdo, didn’t like it and brushed it out when she got home. The phone rings. Will the children please do what they’re told for once? I can’t talk now, Ev. I’m way behind. Leo, take your boots off before you track in all that snow. Percy deserves his once a year office party. I’m not going to be mad at Percy. Why would I be mad at Percy?

It seems only yesterday Gwen was riding her trike around the house reciting The Night Before Christmas, and now it’s Lily’s turn. Just settled down for a long winter’s. Long winter’s…? Winter’s…? Stop now. You’ll get dizzy. Or go the other way. Ready to peddle to the ends of the Earth and for what? Once, when she was talking to Evvie and heard the car, she told her sister she’d read in a magazine that if you’ve been lollygagging and hear your husband drive up, you’re supposed to leap up and start frying an onion. Something sure smells good, he’ll say. I’m going to try it. The next day, she called her back to tell her it worked, and they laughed like anything.

Do you think the centrepiece looks too stiff, Gwen? You’re the artistic one around here. All right, go on acting like you don’t care. But don’t think that attitude is going to get you anywhere.

One thing Gwen knows for sure is that her mother’s dearest wish is for her children to be dressed in perfectly ironed blouses, posed gracefully around the piano when their father comes in, carol books open to Hark the Herald. Snow, definitely snow falling past the bulbless light fixture on the front porch. The second you hear tires on the driveway, plug in the tree. Chuck the bike on the landing to the cellar. Whoever heard of riding a bike on the hardwood floors? At least this year the tree doesn’t have to be tied to hooks on the wall to keep it upright. When their dad opens the door, takes off his fedora and wipes his steamy glasses, their mother reaches up to kiss his cheek. The car waits outside in the yard like the horse at the cabin in the blue painting above the piano he stares at from his chair when he’s had a bad day. That man has everything he needs, he says. The cabin is on the Prairies, somewhere with open skies and a wide horizon. Gwen points a pulsing finger behind her mother’s back to make sure he sees the mistletoe above him, which is nice of her considering. Oh well, she’d thought, when he said about walking across the Russian steppes. I’ll do it for him. He winks and kisses her mother’s cheek back so she can have her perfect moment.

On Christmas morning, when they head down the stairs in procession youngest to oldest in their slippers and dressing gowns, the holy lights dazzle on the be-all and end-all perfect tree. Storybook dolls dressed in fur-trimmed coats lead a decorated elephant past a gingerbread house. Figurines in silver skates whirl on a pool behind a miniature town on the tree skirt. Someone on a corner is singing Silver Bells. Why can’t it always be Christmas?

Gwen gets a powder blue corduroy skating dress and cap trimmed with white angora blanket stitching. Lily gets the same outfit in rose and a doll with skates dressed in the same ensemble. Made by Mrs. Santa Claus. Lunch is pick-up, which means they don’t sit down at the table. At five sharp, their dad leaves for Laburnum St. to collect his parents. Is the bird done? Will someone wiggle the arms and see if the juices run clear? The vegetables and turkey aren’t ready at the same time, but what can you do?

After dessert, Mother folds the wrapping paper so they can use it again next year, arranges the towels and sweaters back into their boxes for display. Their dad’s present to his parents is to be saved until after dinner, but they have to give mother one sec to make sure Lily’s down. She’s completely overtired. Too much Christmas.

He waits patiently in the living room to present his pièce de résistance, not that dinner wasn’t. The only trouble with dinner is that it’s over, he says. Lily takes so long to go off they’ve already started on the pièce de résistance without Mother. When she comes in, they’re passing around a glossy photograph of a large white farmhouse with gingerbread trim, puffs of apple blossom and pearly everlasting in the background. Dad pushes his glasses back up his nose as if Christmas is only an excuse for what he’s got up his sleeve. Grandma Killam holds the photograph carefully by the edges. She’s not to worry because things have been worked out fair and square for everyone. Mother slides into her chair as if she’s late for church and they’ve started the first hymn without her. What’s been worked out fair and square for everybody? she asks.

I’ve been over the details with the advisory committee, their dad explains. The money’s going to the soldiers’ relocation fund for the boys’ education when they get back so our contribution will be to a good cause.

Mother picks up the photograph as if it’s someone’s unfortunate x-ray. The three people sitting in front of her are from back east and have no idea how things are done here. You can’t do this, Percy.

Of course he can, says Grandma. We’ll manage a small place like this. We still have some pep.

Would you excuse us for a moment? Mother takes dad’s arm into the kitchen. What on Earth are you doing with pictures of the Yoshito farm? Whatever committee you’re talking about, it’s not theirs to sell. We’re looking after the place for them.

What do you mean, we’re looking after the place? Since when?

Well, I’m not exactly, but you know perfectly well Isabelle’s been.

Oh, Isabelle.

You didn’t think to discuss this with me?

Ada, my parents can’t live in an apartment, Percy says. Scarborough’s a hobby farm compared to what they’re used to. It’ll give dad a new lease on life. All mother can say is how badly she feels that she took dad away from the farm. If I hadn’t picked it up, someone else would have. It was going for a song. Let’s talk about it tomorrow, Ada. We don’t want to spoil Christmas. At least it’s still in the family.

18.

January, 1943

What I want to know is how the hell Percy found out about these properties I was going to say up for sale, but they’re obviously up for grabs. Your in-laws, I can understand them turning a blind eye, but Percy, well now, Percy. I thought he said you didn’t have any money. Why do you think I’m here trying to keep things up for them? Auntie stands above a pair of old gloves in a wheelbarrow at Scarborough; rakes and trowels lie on their backs beside a pair of open hinges. She looks weak and shaky as she tries to yank dried pea vines from a net trellis, but they get even more tangled up. Maybe she didn’t get any presents this year over here, that’s her trouble. Where did she have Christmas dinner? In a ditch? The ground is littered with fir branches.

It was nothing to do with me, Mother says. I didn’t know anything about the sale.

You never do, Ada. That’s your trouble. That’s what you get for marrying a man from back east.

You’re alone too much, Isabelle. You should come back to town.

What’s town got to do with anything? Who the hell sold it to them?

Percy bought it from the custodian.

Percy did, did he? Christ almighty.

Isabelle, the children. Your language. I know it’s upsetting. I didn’t know anything about this until Christmas Day.

Do you do this on purpose, Ada, or are you really that obtuse?

I’m really that obtuse.

They can’t have the place, whatever Percy thinks. What am I supposed to tell the Yoshitos?

I don’t know, says Ada. Do you know where they are?

I wish to hell I did. I’ll have to come to town and look at the documentation. Percy can’t do this. Property deeds are property deeds.

Not in wartime apparently.

Auntie walks over to a stump to change out of her gumboots, smashes her hat on her head. I have to go to work, she says. Walk with me if you want. At least they’ve given me my job back.

It’s not your responsibility, Issie. I don’t think there’s anything you can do about it.

It certainly is my responsibility. They left me in charge. How could it not be my responsibility? And don’t think

you’re going to get out of it that easily. He’s your husband.

The store with the post office in it looks like a railway station—it’s supposed to, the dancehall is like the roundhouse where the train gets turned back in the other direction. There’s a picture of it in the hotel lobby. Once she’s behind the wicket, Auntie looks even worse. Her cheeks are hollow, and her eyes so dark it’s as if the pupils and irises are one large pupil. The whites are the irises. The dark circles outside the whites are like a raccoon’s. No blue light through her eyelids now. The light from the bulb makes her skin look as if she’s growing in the mail wicket like a mushroom.

Children aren’t allowed to go to funerals when they’re open casket so they weren’t allowed to go to Grandma Gallagher’s, but after the service, because their dad is an engineer, he had to go back to the crematorium to fix the burner which wasn’t working properly. Maybe he should take this scallywag with him. Oh for Pete’s sake, Percy, do what you like. Neither of you gives two hoots how I feel, Mother’d said.

It’s too bad Grandma Gallagher died, but it was still a special Sunday morning when she and her dad drove along 41st to Victoria Drive, turned up a driveway past mounds of sloping grass with gravestones propped like place cards. A burly man in overalls stood outside the crematorium, which looked like the witch’s cottage in Hansel and Gretel. Something’s haywire with the installation, he said, which made her dad roll up his sleeves and crouch by the burner. Her dad says he doesn’t mean to prevail upon the good offices of this fine establishment here, but if it’s all the same to them, he’d like to give his daughter a little education.

When he finished the repair, he went over to the corner and flipped open the lids of a bunch of coffins lying against the wall like bass cases. Whoever was in those boxes had nothing to do with people. More like huge dolls that’d been left in the sun to dry. One fellow looked like he tried to be a man once but got so discouraged his stiff grey hair turned into a bird’s nest. Another wore a pinstriped suit like the man at the corner who wanted to show them his dolls in a suitcase, but when they told their mother about him, he wasn’t there anymore. Another might once have been Grandma Gallagher, but all that was left of her was a sucked-up face, a satin blouse and a cameo brooch over a few sticks. When her dad started up the burner—the attendant said he knew he would get it going—they slid the coffins into it one by one like logs into a sawmill. Gwen was to sit on a stool by a peephole so she could peer into the burner like someone checking a jail cell. You watch, her dad said. The spine contracts as the body burns, and the corpse sits up. It did too, as if it’d forgotten to tell somebody something. There was a shelf lined with urns over against the wall. If they didn’t clean the bottom after each burning—and they didn’t—how would they tell whose ashes are whose? That’s all there is to it, her dad said on the way home. You get born, you live and you die. It happens to everyone, and it’s just about as ordinary as you can get.

19.

July, 1943

For heaven’s sake, Gwen, Isabelle’s moved to the hotel, and there’s nothing anybody can do about it. I plain need you to go to Scarborough and get some corn for supper. What do you mean the place looks like a half-erased drawing with the one underneath showing through? What kind of a thing to say is that? Get cracking.

Down at Sandy, Frances is still cluelessly pulling up the rowboat half a dozen feet at a time and leaving it stranded. Horseshoes clang in the pit beside the number one tables. After the lagoon causeway, Gwen stays on the path in front of the hotel that hits the trail slanting diagonally up the south bank of Deep Bay. Past the cornfield down the driveway to the Scarborough house where she stands tapping at the kitchen window to alert Grandma Killam who says she wants to be called Grandma Flora now that she’s moved to the farm. She stands by the sink in her bibbed apron, peering at her thumb. Glad you’re here, Gwendolyn, she says. See if there’s a sliver in there, would you, dear? Poke it with the needle, it won’t hurt. Over a bit to the side there. That’s it. One thing I hate about living alone, you have a heck of a time taking out your own slivers.

But she isn’t living alone. Where’s Grandpa Lyndon?

The amount of cleaning we’ve had to do around here, we could have used an army. Someone left behind a perfectly good table saw. You’d think you’d be able to count on a day or two for the weather to stay fine enough for the hay to set, but no. Couple more days of this mucky palaver and you might as well make haykraut out of it.

Grandma Flora’s clearing out some dusty sketch books on a high shelf, finds an old pot behind them, opens the lid and peers inside. What’s this, Gwendolyn? A bunch of old ash. Pour it in the garden for me, will you dear?

I can’t do that, Grandma. That’s a dead person. I saw some urns like that at a place where my dad took me to fix a burner.

What was he doing taking you to a place like that?

Teaching me.

I see. Well put it on a shelf back in the shed then.

When Gwen comes back, Grandma Flora goes into the dining room, takes off her hat and lays it on the table. Her head is almost bald on top. So that’s why she keeps it on all the time.

I’m supposed to get some corn for supper, Grandma.

We can do that. The corn isn’t doing badly considering the amount of sun around here. How fresh do you think fresh corn should be?

The same day?

Grandpa Lyndon comes down the small hill from the orchard like he’s on skis and the snow’s so rotten each step might take him through to his knee. His chest seems to have shrunk; his pants come halfway to his chin, and the braces only have a short way to go over his shoulders to get to the other side. Flora takes a pot from the cupboard, says she’ll get the water going. Take Gwendolyn with you, Lyndon, let her pick a few ears. Make sure the tassels are dark brown.

When they get to the field, the corn is not as high as an elephant’s eye, but it’s getting there. What are we waiting for, Grandpa? says Gwen.

For the water to boil.

When the window opens, Grandma Flora calls out. Now! Grandpa Lyndon waves to her and starts peeling the ears, nodding at Gwen to do the same. They run back to the kitchen tossing husks as they go.

Now that’s fresh, Grandma Flora says, popping the cobs in the boiling water. Four minutes is all these babies are going to need. She tosses the colour pouch to Gwen to mix into the margarine before they scrape it onto the edges of their plates, sprinkle the salt and pepper and spread it on the corn. They hold the ears up to their mouths like mouth organs, fasten onto each other’s eyes and nibble fast to see who can get to the end of the row first. Their rabbit teeth remind Gwen of the way Isabelle bared hers when she was standing in front of this very house, so upset her ears looked like they might start growing out of her hat like a horse’s. Eat up, Gwendolyn. What’s the matter? Isn’t it fresh enough? says Grandma Flora and winks.

Now what’s she supposed to do? She likes being with these Killam grandparents. They’re funny and nice. Where’s Molly? Down on the beach barking to beat the band. Grandma Flora pushes back her chair, grabs Gwen’s hand, and the two of them charge down the path, hollering at the dog who’s swimming overtop a struggling deer. Hauling up over its backside, she pushes her prey under water as the antlers circle and disappear. Get up here, Molly! Molly goes on hulking, slowly sinking the deer, intent on nothing she knows. She swims back slowly, not caring when Grandma Flora swats her. Hope nobody saw, she says. The dog shakes water everywhere. You’d better leash your dog up, Gwendolyn. Expect they send the RCMP round to shoot dogs for less than this.

So now Molly’s her dog the way her mother tells her father to do something about his children when she’s mad at them. Molly, you’re a bad dog. You’d better learn to behave if you’re going to stay here at the farm. She’s still got that money she was saving to help Auntie buy Scarborough. Auntie said it wasn’t enough and to keep it. She was going to use it to buy that Hawaiian bathing suit top she saw at the store, and make a hula skirt from t

he bulrush grasses down on Miss Fenn’s Rocky so she’d have a costume for the masquerade after all. But, instead of spending it on herself, what if she gave the money to Billy and asked him to stop bothering Leo? Maybe that would make her a really really good girl and it would be okay to like being over here with her grandparents once in a while. Stay, Molly, I told you to lie down and stay.

When she gets back to the cottage with some corn, it turns out Leo’s had one of his nosebleeds so she and Aunt Evvie have to take him to the First Aid Station by number two grounds, a regular cottage with hanging flower baskets, except that it has a red cross on the door. There’s always a sprain or fracture in the corner waiting to get bandaged up. Dr. Stan, the new First Aid man, does everything with his right arm. He tries to distract Leo with questions about his comic book collection—how’d he know about his comic book collection? This boy’s to go home and rest in bed for an hour, in case, he says. In case, what? says Leo. Never mind our Leo, Aunt Evvie insists. I’ll never forget the time. He couldn’t have been more than four. Come on, Leo, I said. It’s time for bed. But I went to bed last night, he said. Isn’t that…?

When Dr. Stan looks out the window and sees Jeanette climbing up the stairs, the two of them look like they’re going to fall out of their faces. They say hello like people who know each other but are pretending they don’t. The next morning Leo has earache again, so Dr. Stan has to come over, his whole warm height rising up the attic stairs as if he’s coming up an elevator from a mine.

All ready to knock ‘em dead tomorrow, kiddo? he says to Aunt Evvie who looks like she’s about to tuck one knee into the other, cock one hand on her hip, and the other behind her head hubba hubba ding ding. We all know you’re the glamour girl of the family, Evelyn, says Mother. Wouldn’t lift a hand to wash a dish if she could help it. Aunt Evvie came back from the First Aid Station saying she’d made up her mind to ask Dr. Stan to be her doubles partner. Do you suppose he can play tennis with that hand? Mother’d asked. What hand? Now she looks at his carved fingers fastened on the wooden branch railing to the attic as if she’d accepted a dance with a man when he was sitting down and only realized when he stood up that he had a wooden leg. Maybe the only thing he needs his left hand for is throwing up tennis balls before he hits them.

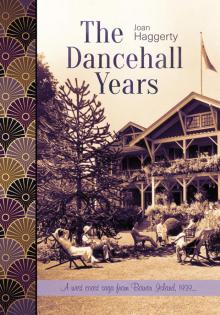

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years