- Home

- Joan Haggerty

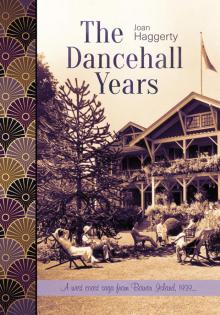

The Dancehall Years Page 8

The Dancehall Years Read online

Page 8

Well, congratulations, Isabelle.

Thank you, she says.

Can I be your flower girl, Auntie?

10.

Gwen is prancing her knees up and down, pointing her toes like a pony. Someone has to come with me to Sandy, she says. When can you, Auntie? I need to give Frances back her whistle.

Don’t worry about that, Gwen. I’ll talk to her about the whistle. What’s Frances doing here anyway? Isabelle says to Ada who’s washing dishes. I thought she was going to waitress at Britannia Beach for the summer. They’ve got all those miners to feed up there.

Not after I told her the lifeguard job was free. You can wait until one of us is good and ready, Gwen. Do you have to go to the bathroom?

You told her that?

Why wouldn’t I? She has to make a living same as everyone else. She must be doing something right. Gwen can’t get enough of her. Those beach rats, people say, they’d sleep down there if you let them.

The next night, Isabelle crosses the porch of the Girls’ Dorm up behind the hotel, passes through the lounge and down the long corridor perpendicular to the living room where she finds Frances in her room gazing longingly at her friend, Jeanette, who’s on the cot opposite, head so far down on her chest all you can see is the part in her hair. When Isabelle comes to the door, Jeanette widens her eyes above her receding chin, opens and closes the fork and spoon she’s holding between the fingers of one hand. Want to see how to serve a mashed potato? she asks, twirling the fork, then pushing the prong tips along the belly of the spoon to scrape the pretend spud off the plate.

Ha! says Isabelle.

This is Jeanette, Frances announces proudly, as if the object of her affections is a chickadee with a frosted tiara and necklace because she’s blown cold air into her feathers all night. When Jeanette has to go back to her own room to get ready to go to work, so much of her admirer goes down the hall she doesn’t notice Isabelle’s bewilderment and misery.

I have to talk to you, Fran, says Isabelle. It’s to do with the man whose job you took.

I didn’t take anyone’s job. Frances drags her eyes back to the room. He was Japanese. They’ve all been sent away.

Isabelle sits down where Jeanette had been sitting, which is maybe why she’s finally noticed. I love him, she says. I spent the winter here, and we were together. I’m in trouble.

How do you mean, trouble?

What it sounds like.

The fear in their eyes says it all.

Nobody knows?

Nobody. Ada said you had a waitressing job lined up in Britannia Beach.

I did. But lifeguarding is what I’m trained for.

Has anyone else taken it yet?

I don’t think so.

Maybe I could pretend to take that job. Better money than the post office I could say. Do you think your cousin would mail my letters to my father if I sent them there so they’d have a Britannia Beach postmark? I heard about a place in Blaine I could go to have the baby.

Then what will you do?

I don’t know.

I think she’d do it, considering… But aren’t you scared?

I’m terrified.

What are you going to do for money?

I pawned Takumi’s whistle for a start.

Oh, right. Will that be enough? I’ll loan you some.

I’ll pay you back, Frances. I really will.

11.

Gwen stands at Auntie’s bedroom door watching her lay out five-and ten-dollar bills on the bedspread like a solitaire hand. Ten, fifteen, twenty, she counts. Not enough. Not nearly enough. You’d think a solid silver whistle would be worth more than that.

Maybe Auntie wants to buy the Yoshitos’ house so the two of them can go live there and be alone all summer long. In the magazine ads for Community Silver, the model only gets to lie in the grass and have stars painted in her eyes when she has an engagement ring on her finger. So it must have been that man, Jack Long, who was lying with Isabelle in the meadow below the dancehall that night, but it couldn’t be because Takumi’s the only one she lets stroke her arms from the sockets to the tips of her fingers.

Here’s our girl, Takumi and Auntie always said, reaching their hands down from the tree platform to help her up. The water wants to hold you up, there’s nothing else for it to do. Teaching Gwen to float, Takumi always smiled back at Auntie on the beach as if he wanted to lift her dress up over her head so mother-may-I would let her go out to swim. When he slides his hand from under her own back, she holds her arch for all she’s worth so she can stay floating. Being with the two of them is like when you have a new friend and decide to walk her home. I’ll walk you back, one person says, but when you get to the other person’s house, that person says now I’ll walk you back, so it’s like the polite twins who never got born because one kept saying to the other after you. Later, she’s a bridge between Auntie and Takumi’s hands as they walk home down the resting rock hill. Good floating, they’d say laughing, swinging her between them.

Gwen’s supposed to laugh too, so she does.

She’ll cry, too, if that’s what they want, because even if Isabelle’s sitting in her room counting out her money like the king in his counting house she obviously doesn’t have enough. In her cave down on her beach, Gwen checks to make sure the special quarter, which she can never spend because it belongs to the boy who sings for the open-air interurban at 41st and Dunbar, is still there. The passengers throw money at him. It’s okay to help him pick it up, but once she slipped a quarter into her own pocket when he wasn’t looking, and one of the dark quiet people from the Reserve who sits at the back of Mr. Pyatt’s store saw her. His hat was narrow and had an Air Force crest of wings on it.

That night, the glow shines under the door of Leo’s partition, which means her brother’s reading with a flashlight. It’s a great life if you don’t weaken, their mother says. But of course you do. Grownups act as if, when night comes, they’ll have a better life without the children there. Her dad’s words steam up through the gap around the chimney. Does anyone know where the dinghy’s gone? It happens, says Isabelle. An especially high winter tide, I guess. Have you noticed how good Gwen’s swimming is getting? When grown-ups say things that let children know they like them, they grow in their sleep.

When she sneaks into his room, Leo wants to talk about the man in the story he’s reading who escaped the German army and became part of the Resistance, whatever that is. If you’re part of the Resistance and speak German, evidently they take you to a hotel somewhere in England where they brainwash you, which must be like having your mouth washed out with soap. After they empty you of whoever you were before you came to Allied territory, they fill you up with everything they know about some German person who died. Then they wake you up in the middle of the night and ask you questions.

Say you’re him, Gwen. What’s your name? Where do you live? What are the dates of your children’s birthdays?

Is that rain or leaves? Rain. The toilet flushes. The silence shifts.

The amount of equipment that’s going out of here by train, her dad says up through the chimney, all Jerry has to do if he’s got any brains is land a couple of plainclothesmen on the coast. Get them on the train to Lytton, assign them to blow up those two bridges that crisscross the Fraser. That’ll hold up things for a while.

You’re not supposed to say things like that, Perce. Jugs have ears.

These children of yours are jugs? Raising kids is impossible. Whatever you do is wrong. You say too much, you’re interfering. You don’t say enough, you’re irresponsible. I give up.

You don’t mean that, Percy.

I do, yes I do.

12.

Take Leo. That is, if you can find him. It’s suppertime, and Gwen’s supposed to be fetching her brother from the tearoom as usual, but the Alex is coming in; someone who’s catching the boat has given Leo a bunch of free pinball games, and there he is up at the helm, pulling levers and yanking side arms smashing s

ilver balls against miniature lighthouses till the cows come home.

It’s supper, Leo, she says. You have to come home. Two shakes of a lamb’s tail, he says, flipping another lever. Get the ice cream and wait for me on the verandah. She does—it has to be vanilla—she sits on a bench holding the folded box by its wire purse handles. Miss Fenn could learn a thing or two about makeup from the chickadees here, the way the shadows on their eyes sweep deftly back at the sides, black fading to white. They jump around on their stiff legs, pecking crumbs from leftover hamburger buns.

Drat, says a man in the phone booth when his change falls between the slats in the floorboards. There goes my nickel.

The ice cream’s starting to melt, Leo. Come on.

All right.

They start for home, but wouldn’t you know it, at the bottom of the bluff, the big boys, Billy Fenn and them land in a whoosh, careen in front of Leo like dogs that don’t know how to go straight on the road. Hey Professor Snodgrass, got anything for us today? Billy’s face is flat and pale like his father, George Fenn’s, and his sticking up hair is so blonde it’s almost white. A couple of nights ago, Billy let Leo join his softball team, and Leo traded him a Captain Marvel comic for only a Captain Marvel Junior so you’d think maybe they’d go easy, but no.

My brother is smarter than all of you put together so blow it out your ear, why don’t you? she says.

Don’t say anything Gwen. They’ll get you.

They will too. You have to stay clear. They’re supposed to make allowances for Billy because his mother died, but why should they when he waits until you have the very last grain of sand in place on your sandcastle before he kicks in the turret.

Keep walking, keep looking straight ahead, says Leo.

Don’t think we don’t have our eyes on you, Professor Snodgrass. You too, Gwenny-Henny.

In the summer, they’re not supposed to get up before the big hand is on twelve and the little hand is on seven, but even Lily’s way past telling time that baby way. Why can’t I come with you? she says. Shhhh. Go back to sleep. The way Gwen’s thinking, if one of the dancers ended up having to call home in the middle of the night to say he missed the boat, he’d likely be reeling around and might end up dropping change between the floorboards in the tearoom phone booth. From watching boys play war, she knows how to worm her way into the crawl space under the verandah below the phone booth, scrabble her nails in the dirt to unearth the shiny edge of a nickel, and then two dimes and a penny. Not bad for starters. She’s not the only person out this early though; when she crawls out, there’s Mr. Fenn wandering around in the bush, combing through the salal with a stick.

From the platform on wheels down on the wharf used to boost the gangplank to the steamer at low tide, there’s a good view of the blackboard on the shed that announces the day’s picnics. Today is Eaton’s; great, they’re a good picnic. Crowds troop from the wharf along the Government Road to number two grounds behind the post office, where the concession stand man is supposed to tear the picnickers’ tickets in half before he throws them on the ground, but lots of times he’s so busy prying caps off pop bottles and passing Dixie cups over the counter he forgets to tear them. They’re using purple today. Good, they’ve got lots of purple. When the picnics go down, she and Leo pick the untorn ones off the floor, go home and bottle them in jars in the attic. Hudson’s Bay, 1940. Longshoremen, 1941.

Once they know the colour, they race down the hill, tag the resting rock, rush into the kitchen and up the stairs. One of these weekends, please will Percy make a railing for the attic stairs. Lily almost fell down them the other day. Back at the dancehall, Gwen and Leo set up a booth on the porch where they sell the purple tickets to the other camp kids. Three for a penny. Seven for two pennies.

Gwen’s got her swimming lesson after the picnic, and she has to go even if it is raining. She won’t melt. She’s not butter. On Sundays, when they go to Sandy for their morning swim, her dad says he’d rather be heading for a nice clean lake on the Prairies where he wouldn’t be obliged to swim in salt soup, but beggars can’t be choosers. Billy and his boys are down at the hot bench on Sandy, pushing each other on and off as usual. Leo’s thin top lip pushes forward when he sees Billy and his gang; he stands tilted forward, eyes fixed on the ground, concentrating on the farthest star he can find in his mind. Billy lands in front of him, lurches into his walk like a held-out coat. He holds up his hand and looks at his nails. Only a day late. That’s not too bad, Leo. Not by all accounts. What do we do to poor sports, eh boys? Get over here, Leo, we have to take your fingerprints. Think if it was your tongue. Another time, they shoved her brother under the cobwebby back dancehall stairs and stuffed poisonous mushrooms in his mouth. After they left, she had to coax him out like a scared puppy, his mouth full of guck like cotton batten sticks the dentist forgot to take out. He spit and crawled along the ground. The whole day he kept spitting. Are you sick? Have you got earache again? they said at lunch. I’ll take him to the wharf, her dad says. He can help me put the boat up on the ways. Stop spitting, Leo. You think it looks tough or something?

Billy marches Leo over to the bluff, lifting his knees one after the other from behind with his own. Get his bag off him. Twist his arms behind his back. We’ll take him prisoner. Skin burn him. Butt him up the bluff. They prod him with their sticks and march him up the rock, the back of his jacket pulled over his head. They’ve done this so many times Leo knows the way blindfolded.

We’d better make sure this kid knows we mean business, says Billy. We’re still in business, right, Leo? Got any of those pellets left there, lieutenant? When you’ve got rats, you don’t want escape holes. This prisoner has got five on his head alone. When they twist his head, Leo concentrates on another star, trying to get high enough to see himself down on the bluff where the front of one of his torturers’ pants has stretched hard. They push his head to the other side. All right, prisoner. Let’s have the secret admission papers.

They’re in my paper bag, says Leo. He looks over his blindfolded shoulder even if he can’t see.

These are coded correctly, are they, soldier? You’re not leading us on a wild goose chase. Otherwise, it’ll be double or nothing.

The tickets will get you past the enemy line, says Leo. They’re all disguised today as Eatons’ employees.

That was kind and considerate of you, soldier. Wasn’t that kind and considerate, boys? Hand over that filthy paper bag of yours. Keep this deal under that twerpy Boy Cubs cap of yours, Leo. You too, Gwenny-Henny. If you say anything to anybody, we’ll get you worse than ever.

They leave Leo flat on his back, panting, ankle noosed to a tree. He can’t breathe through his nose because his nostrils are stuffed with pussy willows. She has to help him turn on his stomach so she can get his leg free and help him home.

At Sandy, there’s a sign on the First Aid Station bulletin board announcing a sandcastle contest. First prize twenty dollars, and all you can eat for dessert at the Shack Café. A chance to blow the whistle on the Lady Alex. Good, Gwen thinks. She’ll win and find a way to talk to the captain and tell him to make sure Hitler isn’t trying to get on the boat. And she’ll be able to save the money to give to Auntie.

She has to get on with finding building materials to go with the curved stick for the main sand house beam she found on Miss Fenn’s Rocky. Smaller versions to fasten into the beam for rafters. A piece of tin painted green, scooped scallops around the edge to mark the roof, wet sand walls that drop straight to the ground.

She’ll use the blue plastic bowl from the cupboard for a swimming pool, sprinkle rose petals in it when she sees the judges coming. The blossoms will have to be cupped and floating, not waterlogged and sunk.

The sandcastle contest judges are Frances and that waitress she’s so crazy about, Jeanette Ann somebody. The two of them, dressed in white skirts and navy blue blazers, are bent over some stupid half baked Lady Alex sogging along the sandbar, looking more like a lump of dough than a boat. As the

y zigzag from one side of the sandbar to the other, Gwen keeps a close eye on them, waiting to strip the petals from the stems at the last possible moment. But, instead of crossing the sandbar back to her side like they’re supposed to, what do they go and do but continue along the same side toward an even worse Lady Alex, so it’s going to end up like in school when the teacher calls questions up and down the rows, you’ve counted ahead and figured out the answer to your question, but then she changes her mind and starts working the room lengthways instead of across. By the time the judges get to her, all the petals have sunk.

For heaven’s sake, Gwen, says her mother when she comes to pick her up. It’s not the end of the world. You learn from what you did wrong and do better next time. Is it part of sandcastle contests that you use mostly sand?

Second Childhood, My Eye

13.

What many on the island know but pretend not to is that, like many others during the Depression, George Fenn had been determined to find a ruse to get by, and you had to say he latched onto a good one. He first got the idea on one of his excursions over Scarborough way when he’d watched Shinsuke Yoshito hauling sack after sack of potatoes up from his field.

Give you a dollar for a few of those? George said. Shinsuke knew he couldn’t have too many vegetables in his root cellar for the winter, but was canny enough to take the opportunity to begin to pay off the Fenns, so they’d have doubly earned Scarborough and nobody could have a case to look twice at them.

George went home, got his first batch of potatoes cooking, added the barley. Had to experiment to get the proportions right, cheered when the concoction settled down to saccharify. On Sunday mornings, the woods around the dancehall were filled with empty bottles for his product. He collected them in the empty potato sacks and began to save matchboxes.

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years