- Home

- Joan Haggerty

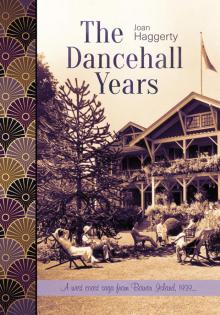

The Dancehall Years Page 29

The Dancehall Years Read online

Page 29

He is. You probably heard how George Fenn’s family used to own Scarborough. It was given to the Yoshitos way back, and the whole time we were kids, George was beating up on Billy because he was angry about being disinherited.

So my torturer is the father of my niece?

Yes.

The next time Leo sees Billy, he’s reminded of the way a house you’ve lived in as a child seems shrunken when you go back to it as an adult. Maybe because Gwen is beside him, for the first time he notices how shifty Billy looks.

56.

As for Lottie, she still walks by her old cottage almost every night to see if it’s for sale even if she’ll never be able to afford it. All she has is her old age pension and the bit of money Takumi still sends her every month. The poor Scarborough house. Everyone at the store’s talking about it. Even that Shima’d shown up and been invited to live there. It’s not only for their sakes she needs to bring Isabelle and Takumi and Shima together; the three of them are the closest to family she has.

Odd, there’s a light in the front bedroom of the Gallagher cottage. Maybe Ada’s up. At Derek’s memorial, when Ada realized Lottie had heard, she looked as if she’d caught a shockingly aged reflection of herself in a mirror. She knocks on the door and goes in. Ada? Is that you? It’s Lottie. But it’s Frederick’s voice that sounds from the front bedroom. In here… When she opens the door, he’s sitting on the bed in front of an open bureau drawer, a white hand-knit infant’s dress laid out on his knees.

Do you have any idea who put this here? I was looking for some old things of Harriet’s.

Lottie sits down on the bed beside him, reaches out, touches the dress, takes his hand. I have to tell you, Frederick. Isabelle had a baby the winter Harriet died. She left her in Blaine at the hospital where she was born. Only, I know now, because she thought the baby died. It was the war; the baby was half Japanese. Her child spent her first three years with me. Her name is Shima. She’s a young woman now, and she’s here.

Frederick looks stunned. Here on the island?

Not at the moment. But she’s here.

Isabelle had a baby? You looked after her for three years and didn’t tell anyone?

I did.

Would you mind keeping an eye on things at our place over the winter?

Frederick folds the dress carefully back in its box. Tucks the tissue paper around it like a blanket. That’s what was wrong with her when she came to Laburnum St. that Christmas all those years ago, he says slowly. And I didn’t even see it. If only Harriet hadn’t been so sick. He looks as if he’s been blindfolded, turned around. When they take the blindfold off, he doesn’t recognize anything he sees. Before Lottie leaves, she takes the silver whistle from her purse and slips it under the lidded cavity in the fireplace.

Blueberries

57.

March, 1977

Have I told you about my great idea for a TV phone-in programme, Mom? At their newly rented house in Vancouver, layers of magazines are glued to the bedroom floor with stale juice and dust. Jenny crawls up to the TV, switches it on, squirms back on her bed. It’s called phone-in-for-death, she says. What you’ve got is someone hanging onto a window ledge by their teeth. People get to phone in. They have three minutes to save the person. If they don’t, they lose their washer and dryer.

Late the night before, Gwen heard her daughter rocketing off the walls on her way down the corridor to the bathroom. Twitching as if ferrets were nipping her heels. What are you doing home at this hour, Jenny, it’s way too late for you to be out.

What are you doing at home at this hour, it’s way too late for you to be out, she mocks.

You do realize I’ve got Maya and myself to be thinking about besides you.

You do realize I’ve got Maya and myself to be thinking about besides you.

I’m going to haul off and deck you one of these days.

You just try.

Never talk to anyone between the hours of three and eight, Dr. Merrick said. It’s mankind’s darkest hour. Say get to bed. Get some sleep. We’ll talk in the morning.

Get to bed. Get some sleep. We’ll talk in the morning.

In the morning, she stands by the kitchen stool, scissors in hand, waiting to cut Jenny’s hair. The air smells like dippity-do, the bloop she uses to keep her dyed blonde points on end. She crosses one orange-tighted leg over the other, fastens a second outsized safety pin in her plaid mini skirt. It’s got to be more spiky, Mom. More off here. It’s not easy getting your hair to defy gravity every day. She leaps up, grabs the dictionary, as if it’s Gwen’s job to get the scissors to whatever spot in the room she’s sitting in. Back on the stool humming. Gnawing a hunk of lettuce. Safety pinning a clipping of the word to her shirt. Big black letters. Right, she says. Pontiff. It’s either a shade of purple or the pope. Let her have her adolescence. If people try to mature too soon, they end up having their adolescence when they’re middle-aged. Pointed glance. It’s all so cosmic and groovy, isn’t it, Mom? You and your granola freak friends. Oh, and by the way, I’m not going to University Hill School next semester. All they’ll expect is for me to be a liberal young adult. I’ve been a liberal young adult all my life. I’m going to be a teenager, and I’m going to be bad. The worst part is I know why I have to do this.

Why do you have to do this?

Because you want me to be fine all the time. I’m not always fine. You’re such a flaming dingbat.

Don’t talk to me like that, Jenny. I’m your mother.

Really? Because half the time I feel like I’m supposed to be the mother.

Great. She’s probably been transferring her need for a matter-of-fact caring voice onto Jenny as well. No wonder she’s angry. No dad’s voice and a mother’s needing reassurance. Maybe she’s been mistaking precociousness for maturity, that’s the trouble. Whatever you do, it’s wrong. One thing she does know: if she tries to hold Jenny back, she’ll leave in a huff like the odds and sods she brings home to hunker along the hall corridor. Maybe she’ll strip for a while, Jenny says now. Save some money, go traveling.

Right and all the money you make would be used to survive.

Just kidding, Mom.

A few more bits of hair on the floor, the phone rings, and she’s up and out of the room. Oh, it’s you, she says shutting her bedroom door. You is probably the boy who called the other night. Jenny’s not in, Gwen’d said. Do you want the phone number where she’s babysitting? Excuse me, Jenny’s mom, did you say four, six, eight…? I’m in a phone booth. No pen. I’m making piles of pieces of paper for each number. I can do four, but don’t know as I can handle eight.

Couldn’t you remember it?

I’m drunk. What’s after the eight?

Nine, I’m afraid.

Maya comes and leans against her mother. Jenny’s back on the stool, swiping at the air around her face. I can’t believe this. He hung up on me. Be an anchor to windward. The future’s a black box.

Maybe you got cut off.

The phone didn’t snap. It clunked.

Keep your voice neutral. Stay in the adult role. Steady her no matter what.

He’s probably wondering what happened too. Maybe you could call back.

Okay. As soon as she reconnects, she’s back in her bedroom. The hair will wait.

Gwen picks up Jenny’s fanzine. It says here there might be a world where a thimble full of matter weighs as much as Mt. Everest.

What’s a thimbleful? asks Maya.

You know what a thimble is. Well, a full one.

I’ve got nothing to do, says Maya.

Don’t tell me you’ve got nothing to do. I’ll give you a job.

For Jenny it’d all started when those eighteen somethings moved into the basement apartment across the street. The day she saw the group of them strut up the basement steps in their black clothes, she sprang from her bed as if she’d been waiting an eternity for her cue. Threw on the old gabardine raincoat she’d found in the alley and headed out.

The night Gwen tracked her down at the Smiling Buddha on Hastings St., Jenny tenderly reached out to help her mother navigate the bodies leaping up and down in the mosh pit. While everyone else had been trying to clean up and salvage what they could from Scarborough, Jenny trailed a scarf around what was left of the living room. Cracked like a live wire if anyone said anything to her. Insisted on starting a second dispute while the first was still in progress.

Down in Birch Bay, Isabelle’s sliding dampened labels off ketchup bottles when Leo phones to ask if they happen to have a beach down there with a long, flat horizon because there’s an important astronomical conjunction he wants to observe. Only one chance every eight years to see the morning star and the evening star on the same day. You have to have a long low horizon to see it.

So a few days later, it’s Leo sitting at the Bide-a-Wile counter drinking a milkshake, telling Jack how they used to think that, because Venus was seen west of the sun the morning of the day it’s also seen east of the sun, the sighting to the east of the sun must be another celestial body. But it’s not, it’s Venus itself. You know that first bright star you see at night because it’s so near us, Jack? We’re going to see it in the morning, and then we’re going to see it again at night.

Is that so?

Would you help me find the best viewing spot?

You betcha.

Jack sets his shoulders back, confident he’s the one they count on to know what’s what on the tide flats.

But in the morning, when Leo knocks on their bedroom door, Jack mistakes him for a guard who’s come to take him to a new camp—further north and cooler maybe. Traveling north through Thailand, he’d crouched in a boxcar holding another prisoner out the door to defecate, the car shaking so badly he almost dropped him.

Out on the flats behind a dune, waiting for dawn as if for an ambush, Jack tells his nephew he’d better try to keep that maggoty soup down, otherwise he’ll starve. Touches what he sees as an ulcer pushing out Leo’s lower lip. The one on his leg has pulled away so much flesh the bone and tendon are exposed. See here? They have to sharpen the spoons he’s brought so he can dig out the ulcerated flesh. I don’t want to cut into you without anesthetic, but we can’t save this leg.

It’s okay, says Leo. I can manage with the leg for now. Remember the planet sighting we’re waiting for, the one we’re going to see again tonight? That’s what we want to concentrate on.

It’s all very well for Leo, but in case his nephew doesn’t know, Jack has more important things to do: he has to plant the nest of termites in the bridge trestle before the guards pull up the rope cradle; he’s late. As a punishment, the guard pushes him back over the bridge where he falls fifteen feet and lands on his head. But now here’s someone holding him up, telling him all he has to do is look up and he’s going to see the morning star that’s also the evening star. Come on, Jack, over there, if you look up, you’re going to see the morning star.

And there it is, shining and beautiful.

In the afternoon, on one of his expeditions to the end of the shelves in the store, Jack stops short, pries up the lid of their steamer trunk, and digs through a lot of old newspaper. What’s the termite nest doing in there? Ash inside instead of termites? You hold me like a vase. I do that?

Where was this, Jack? Isabelle says.

In our trunk back there. If I push it under a beam on the bridge, the termites will go to work and that’ll slow the enemy down for a while.

That’s not a termite nest, dear. It’s a cremation urn, and it doesn’t belong here. I was worried that I might have lost it because it wasn’t where I thought I’d put it.

In the summer, Gwen is fixing up the spare room in the basement of their 20th Avenue rental; she wants it nice so Isabelle can come for a visit and meet Shima, the Yoshitos being her friends and all. The girls rabbit around as their mother tries to manoeuver a futon frame through the basement door.

For once, let me give you jobs, Gwen says, tacking up a couple of posters. Have you noticed how Impressionist posters are everywhere now, Mom? says Jenny, pulling at one end of the futon. Placemats in restaurants, you name it. Like the old fashioned prints of Blue Boy and Pinky at Grandma’s when you were young. As long as you don’t wear that bedspread skirt when Dad comes to visit. They are so lame.

Couple of days ago, Jenny and her friends had gone to Kitsilano beach done up in long dresses and hats with veils. People were offended, she said. I don’t plan to look like I’m a prune when I’m sixty, not that there’s any way I want to live as old as sixty.

After they finish making the bed, well, that’s a diplomatic way of putting it—the girls stand around and watch is more like it—Maya leans listlessly against the kitchen wall. Summer in the city has possibilities for adults; you can go to a patio and drink sangria after a swim, but for children used to the coastal beaches, nothing compares to the forest and the dark green water. Maya holds herself back when she wants something, Jenny pushes forward.

When Eugene comes, they’ll sit at the table with their youngest between them. Do they regress at Christmas? She understands now how Eugene felt about her being a bottomless pit. Will he notice she’s changed? That she sometimes manages to mobilize her abandoned and unrecognized self? Hope so.

58.

It’s a hot afternoon when Gwen and the girls head downtown to pick up Isabelle. An ice cream truck plays Greensleeves over and over as it wheels down the street. No one comes out to buy Revels. The tar strips on the road soften to glue as drivers squeeze more heat waves from their car horns.

At the bus station, Gwen, Jenny and Maya make their way along the bay of Greyhounds until they locate the one from Blaine. They’re late; the other passengers are all off, and Auntie is waiting in the door. Her ankles are swollen from the trip, but the rest of her is the same, all long bones and angles, her thin mouth smaller and tighter with lines fanning out from her lips. Same old leatherette coat and gabardine slacks, a hat crocheted from the sides of beer tins—is it a joke—the girls stare as she hands down a hatbox and a series of plastic bags. Her hair is shorter and drier, frizzed wiry ends perk from the sides of her alarming hat. Don’t anybody lose that, she says pointing at the hatbox. Maya’s still in the fluorescent green bathing suit she put on to run in the sprinkler. Isabelle grabs the hatbox, makes a staccato turn and heads for the terminal. They practically have to lasso her to angle her in the direction of the car.

Oh, she says, when Gwen puts the car in reverse, steadying herself with one hand on the dashboard. Maya fingers the curved discs on her great aunt’s hat to see if they’re aluminum or pretend. They’re aluminum. Isabelle’s breath pops as if from a squeezed bladder wrack, as she leans against the headrest, then smacks her foot on the floor as if there were a brake on her side. Stop the car. Stop it right now, she says. There’s something wrong with the girls.

When she’d turned around, they were smiling like Cheshire cats, but their teeth were bright blue.

It’s okay, Auntie. They’ve just been eating blueberries.

Oh. I didn’t know what to think.

See that parachute over there? Jenny says as they drive onto the Cambie St. bridge. Kind of a half parachute? Black straps are tied over the curve of the ceiling dome. It’s the new stadium. Mom says it looks like a diaphragm in bondage.

What’s a diaphragm? says Maya.

A thing for stopping babies, Jenny says, looking out the opposite window.

How’s Jack? says Gwen.

Maintaining, I think that’s the word. He’s given up smoking, praise the lord. He thinks I don’t know he’s planning to run the lunch counter by himself while I’m away. Dusty white face powder works its way in splotches down the sides of her nose. Did I tell you Leo came down to visit? He was good with Jack. He took him out to see the morning star.

I’m glad to hear that, Gwen says, looking over her shoulder to check the next lane—the girls’ mouths really are startling. Auntie reaches into one of the shopping bags and lifts o

ut a large round zucchini, its eyes and nose cut in triangles, mouth carved in a zigzag pattern like a jack-o’-lantern. Holds it up so it’s staring back at the girls. I’ve grown so many of these I thought I could get rid of one by getting it confiscated at the border, she says. Give the customs officers a laugh at the same time. They laughed all right and let it through. Now what’re we going to do with it?

This is more like the Auntie they’ve heard about. The one everybody said was a riot. Even Jenny’s reluctantly interested, not that anything the adults do these days is worth her attention. Let’s stop at Baskin Robbins, says Maya. You get free tastes of three kinds of ice cream before you have to pick. Mom, stop.

No. Maybe after supper.

The sun’s glinting off the triangular panes of the domed greenhouse on the top of Queen Elizabeth Park as they drive up the Cambie St. hill. It won’t be long until the sunsets have more purple in them because of the volcano in Washington. Isabelle’s hand rests on the swollen zucchini. The ash from Mount St. Helens will turn the moon blue. Blueberries floating in milk have tiny furled mouths.

Maybe it could be a summer jack-o’-lantern, says Maya.

Sure it could, says Isabelle. Why not?

Jenny stares out the window, as if having to wait for her own life to start is unendurable. When they pull up in front of their house, she bolts ahead without taking anything in. Jenny would you just… Gwen says. Jenny snarls and doesn’t look back. Isabelle flashes her niece a commiserating look (oh, it’s like that), passes the zucchini to Maya, who levers it up the stairs on her hip and tips it onto the wide porch railing. Those petunias should not be in the shade, says Isabelle. They’re all stems.

Forgive the mess. The hall is full of bikes and soccer balls. A ring around the living room at kid level. Someday, when she’s alone again, Gwen will have nothing in her front hall but a slim table with a perfectly centred vase of gladioli.

The house is Arts and Crafts style, with the dining room split from the living room by a sliding door. A foundation of handsome stonework. Maya tugs Isabelle down the back stairs and into the garden to show her the zucchini plants growing over the fence, thick stems Gwen tied up so the wide leaves drape down the boards. When the flowers dry and the green tubes engorge, she lifts the baby squashes onto the ledge to thicken. More leaves trail over a net hung on four corner posts to make a shady grapevine arbour with a bench inside that Gwen hopes will take Isabelle back.

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years