- Home

- Joan Haggerty

The Dancehall Years Page 16

The Dancehall Years Read online

Page 16

Wonder what Mom’s made for supper, he says.

Porcupine meatballs, maybe.

Maybe. Gwen, your mother’s going to St. Paul’s Hospital for a few days. For a bit of a rest.

She needs a rest from us?

It’s not you, dear. She has trouble sleeping.

But she won’t stay there for long?

No.

I can make porcupine meatballs, says Gwen. You mix ground round with rice and simmer them in tomato soup.

I’ll look forward to that.

Rain slants across the car windshield the one night Frances is to drive her home—Percy’s got an extra stop now to see Ada at the hospital, so maybe it won’t hurt to trust Frances this one time. Frances’s chipmunk cheek turns up so she can read the street signs lit by the traffic lights. Do you mind if we go a bit out of the way, Gwen? It won’t take a sec. Instead of turning right over Burrard Bridge, she swings the car north. On East Hastings, discouraged looking people sit on curbs, holding bottles inside paper bags, slop through multicoloured puddles from the neon signs. The rain pelts down and bounces off the sidewalk. Frances parks, leaves the motor running. I’ll only be a sec, Gwen. Just wait here.

It’s way more than a sec. Sitting by herself in the car doesn’t seem like a good idea so she gets out, ducks into a vestibule, pulls open the door that she saw Frances go through. But it must be the wrong place because it’s all men in there drinking and talking. But there’s Frances in her synchronized sweatshirt with the crest on the back leaning into the face of a short slim man in a jacket and tie with one foot on the bar railing. Closer up, she can see that the faces at the tables are women’s faces. As soon as you stop looking at the clothes, they’re women. The barman, barwoman she should say, is drying a glass. This little lady might be a touch underage, she says, touching Gwen’s sleeve. The person Frances is talking to is wearing a hat and tie, but when the man turns around, it’s Jeanette.

There’s nothing to talk about, Frances. I don’t want to swim any more. It’s as simple as that. I only came to class in the first place because of you. I can’t always do things your way.

Nothing for Gwen to do but fold up what she’s seen in the back of her mind, take it out later and see what she can make of it. They’re a ways up Burrard when she sees her dad’s Dodge in the hospital parking lot.

I can get out here, Frances. My mom’s in there. My dad’s visiting her. I can go home with him.

I should have taken you home first.

It’s not that. It’s… he’s going that way.

I didn’t know your mom was in the hospital.

She’s just tired.

When Gwen takes the elevator to her mother’s floor, she finds the door closed. Your mother doesn’t like being touched. What were you doing then kneeling with your face between her legs when I opened the door by mistake that time? Now when she knocks and hears her dad say come in, he’s stretched out on the bed stroking her mother’s cheek. I had no idea how difficult your job is, Ada. Lily can’t find her shoes. I haven’t made the sandwiches. Gwen’s got that Stardust on for the hundredth time. Leo’s slept through the alarm, and I’m trying to get to work all at the same time.

Thank you, Percy. That helps. They sent a psychiatrist in this morning. He had the nerve to say I’m depressed because I think you’re having an affair.

The intimacy of their laugh then; she’ll remember the trust in their voices until the day she dies. So that’s what marriage is like, she thinks. That’s what you get. Their seeing but not seeing her gaze makes her feel safe. She’s glad they have each other. Her dad gets up, tries to turn the knob on the balcony door. It’s locked, he says forlornly, as if that’s the worst part of his wife being in the hospital.

How are you, dear?

Fine. How are you, Mom?

Her mother reaches for her hand and pulls her close to the bed. Much better. The rest is doing me good.

Will you be coming to the championships?

Of course I’ll be coming to the championships.

She will too. She’s the mother who makes satin hunter and huntress outfits for figure skating shows, ices pink cookies for the whole class on Valentine’s Day. Nobody’s Christmases compare to theirs. Maybe her mother takes on too much like her teachers say she does herself.

How did you get here, Gwen? she asks. Did you walk?

No, Frances drove me.

Her parents look at each other as if to say: oh, her.

Well, you’ll be able to drive home with dad.

Vancouver’s Crystal Pool is built out into the sea; a balcony with potted palms lines three sides of the rectangle. In the locker room, Frances leads Gwen past an array of elaborate bathing suits, bras and Mardi Gras headdresses. Satin capes with the swimmers’ names scripted in sequins. Peacock feathers. Someone’s hosing down the floor. She marches her through a gauntlet of professional-looking swimmers to a cubicle at the far end of the dressing room.

Never mind them, Frances says, holding up the starry bathing suit by the straps so her protégé can step into it. The tinfoil stars on her bathing cap fall off as soon as they get wet. The pool seems much bigger than it’s supposed to but it doesn’t matter because her parents are up there watching—no Leo, no Lily, just the three of them alone together. Me and my mom and my dad. It doesn’t matter if she doesn’t come up smiling. Or if she comes last, which she does in no uncertain terms.

In fact, what’s the point of contorting your body over and under the surface of the water, trying to stick your leg up and take it down again? If the audience could see underwater from the side of a large tank the way they do at aquariums, it might be different.

Driving home, her mother turns to her in the back seat, shamefaced. I had no idea what kind of scale this was on, Gwen. I would have made you a costume.

It’s okay, Mom, she says. I learned a lot.

She did too.

Tide in My Ear

31.

September, 1953

Halfway down the seedy block of Hastings east of Woodwards, Lottie Fenn picks her way between scraps of crumpled newspaper and empty cigarette cartons. In the window of a pawn shop next door to an outré nightclub, she spots the unmistakable silver whistle with its odd marking like a crying mouth in a cocoon that Noriko’d given Takumi years ago when he started lifeguarding. That whistle, Lottie says to the proprietor, who lifts it from its dusty velvet backing.

It’s been here a long time, he says. Odd how no one’s asked for it. Don’t often see a solid silver whistle. A woman came in years ago and pawned it.

Lottie tucks the talisman in her purse, continues down to Woodward’s where she finds Evvie Gallagher checking out groceries, her streaked brown blonde hair still kinking over her forehead like nasturtium stems.

Miss Fenn. Long time no see.

Hello, Evvie. Helping your father, are you?

I had a job at the boatbuilding yard, but the war ended, eh?

It did that.

Lottie! Frederick Gallagher buoyantly perks the grapes as he makes his way up the aisle, still debonair in his white shirt and elastic armbands. How are you? We’ve missed you. George said something about Blaine. Are you teaching down there? You look well. We do have pitted dates, he says to a customer. Tea’s here. Nabob? He tucks a parcel into the customer’s cart, nods her on her way.

How are you, Frederick?

I’m fine. Harriet died, of course. It was a long sickness but Evvie’s been a help to me. You know Isabelle’s married? To that nice Jack Long fellow, although he’s… not the same… since he came back from overseas. They’re in Birch Bay. I’m sorry I never managed to arrange a light on your island. Excuse me, this is one of my regulars.

It’d been a long trip from Vancouver to Prince George where Takumi and Shima changed trains for the coast; when they began their descent from Terrace to Prince Rupert, the Skeena opened into a broad estuary between the wide vista of coast mountain and the sea. They thought the long thin striations in

the mountains were cracks of snow but, as they came closer, realized they were waterfalls.

Prince Rupert is a cannery town built above the railway tracks in the deep natural port of Tuck Inlet. The smell of fish permeates the harbour. Thin lines of masts maze the gillnetters lining the docks of Cow Bay. Men on top of railway carriages break huge blocks of ice and drop them in the cars. Takumi found another warehouse that would only need a kitchen and a bit of wiring before he and Shima could move in. Below it, someone had broken a trail and set up an old gillnetter drum for a picnic table. Creeks cascade through deep ravines over gravel and through wet cedar. Wooden stairs rise on an angle, take a break, find their way up another face.

Once they’re settled and find a school for Shima, Takumi gets more work on a fishing boat, makes long runs up the coast past Metlakatla and Port Simpson as far as the entrance to the Khutzeymateen. The man he works for knows from years of experience where the rocks are, the channels he can or cannot go through. He tells them how he was working on his boat when the armed navy guys marched in as if he and his fellow workers had broken some kind of law. They had to put down their tools and go. You weren’t allowed to go back for food and clothes. Nobody had done anything wrong, but the officials issued warning shots if you fell behind.

Takumi and his boss Senji are headed for the area of sandbar near Kennedy Island, known as the Glory Hole, neck and neck with other boats racing to get to where schools of sockeye gather, jockeying for the best position to manoeuvre into what they call the hot spot. Suddenly Senji’s double take is so violent it’s as if a rocket has exploded: the boat beside them might be from a different cannery, but he’d be able to pick her out a mile away. That’s my goddamn boat, he cries. It’s so much an extension of himself he wants to turn the wheel and smash it, better that it’s at the bottom of the sea than in someone else’s hands.

A few days later, he shows Takumi and Shima a photograph of scores of Japanese fishing boats that were confiscated in Vancouver during the war. If I’d known, I would have come down and sunk them, Takumi says equally bitter.

Later, father and daughter rent a trailer on a lake in the Kispiox Valley north of Hazelton. After her father goes out to ski on his own, Shima watches him come back across the lake, a dot that grows larger and more variegated around the edges as he comes closer. On their way into town to get groceries, she skis behind him, the blue shadow of a twisted spruce lengthening as they glide. The straight path of a jet draws a line between the clouds. At the end of the lake, they ride their snowmobile as far as the highway, the back of Takumi’s jacket blowing in Shima’s face. Duck snow-covered branches, leaning to the side to keep the machine level as he widens the trail. She thinks she sees a lynx disappear into the spruce. He tells her they have big loose prints, and they stop the snowmobile to check.

Approaching the Hagwilget Bridge that crosses the deep canyon before Hazelton, they marvel at the power of Stegyawden, the mountain at the junction of the Bulkley and the Skeena. They’re stopped in a highway repair line-up when Shima sees a cross by the side of the road.

That’s to say there’s been an accident there, Takumi explains. It’s a custom in Mexico. I guess someone brought the idea here. So family and friends will think about the person who died whenever they pass.

Did my mother have an accident?

Yes, Shima. She had a serious accident.

He looks so sad she doesn’t ask any more questions.

32.

October, 1956

Finally back on the island, Lottie takes it upon herself to visit Scarborough, where she finds her brother admiring the view from the comfortable wicker chair on the verandah; pride of place brightens his face like the expanse of the Sound under the sun. He looks so at home he could be whittling a stick.

Too bad all you’ve got to look at is that brick wall, Lottie says.

Being needed here matters, eh? he says smugly. Flora said the other day she didn’t know how she’d ever repay me for my help. The place was beginning to feel as much mine as hers. Oh, and did I tell you the new management at the hotel gave me work? I got the contract to tear down the picnic tables near the cottages on the point. Put up a few gates to separate the riffraff from the hoi polloi sort of thing. You can’t dock your boat in the cove anymore if you’re not going to have dinner at the hotel. It’s a new era, Lottie.

So I noticed, she says. They’d raised the rents so high she’d had to take a smaller cottage in the Orchard.

D’you know, asks George. Turns out that Japanese Yoshito kid survived the war in the bush. Showed up here trying to claim his house. You have to hand it to him.

Yes, you do.

Of course we (we?) had to give him the bad news. Don’t know where he went after he was here.

And now look. Here’s Lily Killam coming up the path with her clear, clear skin and yard-length wavy hair. A golden retriever called Roxy has taken Molly’s place. Shy with people, Lily’s nonplussed when it comes to knocking on a neighbour’s door and asking if Duke or Max could come out for a walk. Roxy haunches on the top step as Lily folds herself over her dog, draping her long limbs over the animal’s gorgeous fur.

Roxy’s the nicest person I know, she says.

You can still take the Black Ball ferry from Horseshoe Bay to Bowen Island, but the end of the steamship era put an end to the picnics. The dancehall is closed. Half the cottages are torn down. Get out of here, the summer kids are told when they go to the hotel desk to ask for ping-pong bats or putting green clubs. Are you guests? Whoever heard of having to be guests?

When Lottie’s coming up the entrance path to the hotel—even the hotel is closing, and she’s volunteered to help with auctioning off the furniture and linens—who should be standing in the window done up in his bowling whites but Frederick Gallagher. In the summer, he always attends the fortnightly management meetings; today he’s planning to bring up the question of the light on Lottie Fenn’s island. Come to the window, he says to the new manager, so I can show you where I mean. But the tide’s high, and they see nothing.

Never mind, he’ll come back and show him later after he sees to things at the lawn bowling green. The new manager stands on one foot, then the other.

Mr. Gallagher, the lawn bowling is closed to the public. Since you’re a cottager, you’re welcome if you pay the non-guest membership fee.

I’ve volunteered for over a decade as the president and caretaker, you don’t think…?

But they don’t think. Outside, Lottie stands by the monkey tree mourning the state of the hydrangeas. When Frederick comes out, deadheading is so much second nature to the two of them, they automatically resume with the hotel rhodos, not noticing the new manager frowning out the window.

It’s the limit, Frederick says. I had today’s tournament roster lined up, but they didn’t even look at it. Had the nerve to ask me for a membership fee. I tried to bring up the subject of the light on your island, but they were so high and mighty they weren’t interested. Highhanded tone as well, if I say so myself.

Thank you for trying. I know. Everything’s changed for the worse. This poor azalea, says Lottie. Shinsuke would… I was going to say turn in his grave.

He would, says Frederick. Has anybody heard from them, do you know?

I don’t know. It’s so sad. How are your daughters, Frederick?

I told you about Isabelle… although Jack’s… well, I said. Evvie might take over my job someday, she’s that good at it. She misses her mother. Ada, I wish Ada would stop being anxious about everything. What am I going to do about the lawn bowling? Imagine them having the nerve to ask me to pay a fee. They can whistle for it, I’ll tell you that.

Frederick and Lottie are standing on the hotel lawn with some former lawn bowlers watching the monkey tree come down. Difficult as it is for George Fenn to get under the branches with his saw, the execution takes place. The faces in the crowd are appalled, as if they’re at a public hanging. The emblem of the heart of the place kicked aside by

newcomers who haven’t a clue about its history! When the tree’s on its way down, the stump of its broken neck turned toward them, Frederick takes Lottie’s hand as if to hold himself upright while his stomach lurches down with the tree.

He’d always thought Lottie looked at him for a second longer than she would have if she didn’t care—sometimes he’d sit on the Point Point hoping that his devotion to Harriet might stand him in good stead with Lottie. And now he wished that their connection could help make up for the devastating loss of the tree—she was sure to squeeze his hand back—impossible to think of courting someone whose hand didn’t feel right. It’s too bad that Isabelle doesn’t have children, he says. And Lottie, who’d been wondering for months if the right moment to tell him about his granddaughter would ever present itself, is so taken aback she withdraws her hand.

So she doesn’t like him.

She would have been the only neighbour on the point that winter Isabelle spent on the island. Maybe Isabelle complained to Lottie—warned her?—how harsh and demanding he was. There’s justice to it, but in the glaring afternoon, the monkey tree flat on its back, his hopes for Lottie dashed, he feels that his days are as numbered as the designated lots in the subdivision that they’re proposing to create from the dear old resort.

33.

December, 1961

What’s all this? Percy says at Blenheim St. going through the pile of mail by his plate. At Christmas, he picks up each card, glances at the name, turns it over. Never heard of them. Never heard of them. That’s not funny and you know it, Ada says. Of course, they bought the Blenheim St. house so the children could live at home and be close to the University. Did Gwen just figure that out? At supper what’s all this turns out to be a letter from the Union Steamship Co. informing the Killams that the company is turning over their shares to a firm that’s interested in selling the summer cottages to the long-term renters.

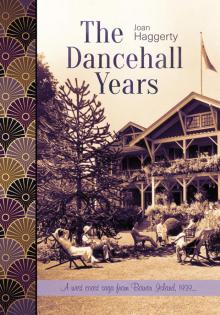

The Dancehall Years

The Dancehall Years